|

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

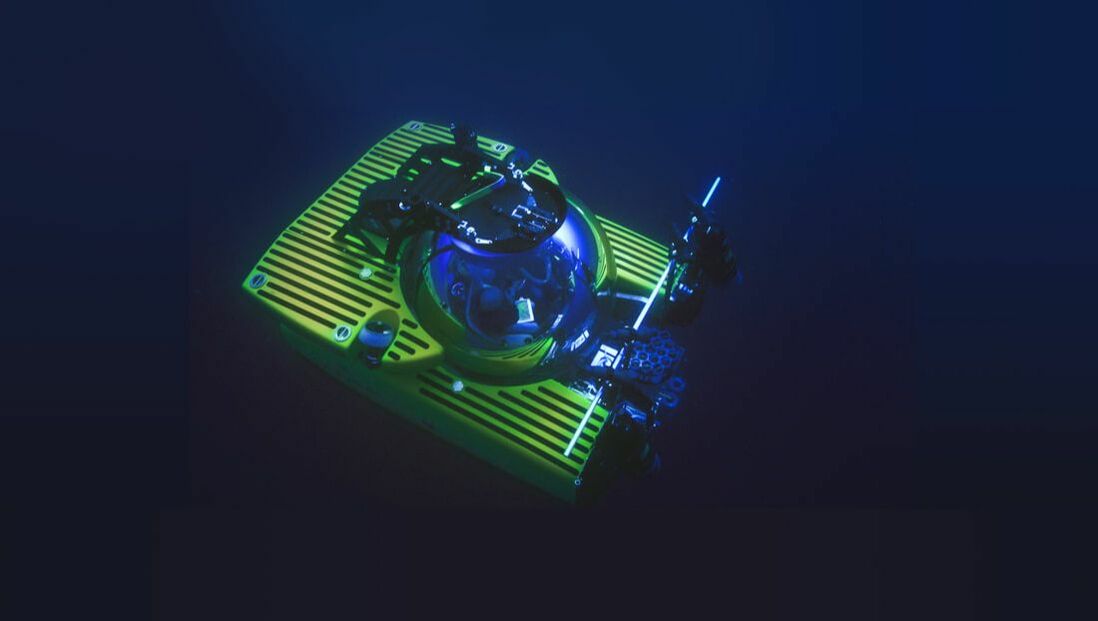

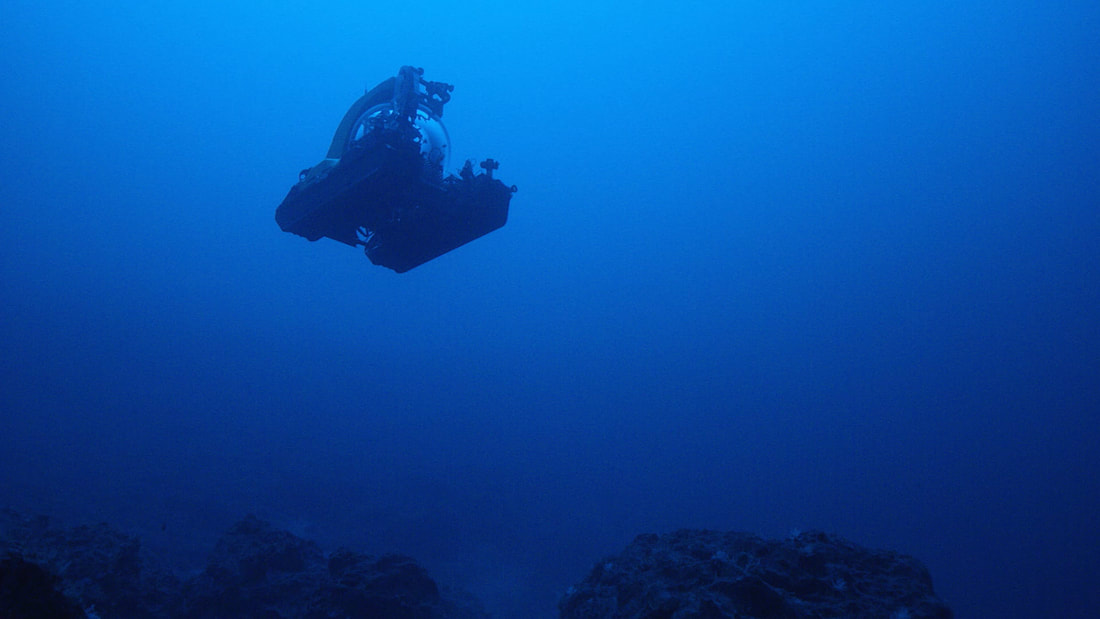

Field Director Mark Dalio: This video was part of the OurBlue Planet digital campaign that we at OceanX coproduced with BBC Earth, which brings to life the incredible stories, videos and photography from the unbelievable world of the blue planet and the scientists, researchers, crew and filmmakers who explore it every day. For Blue Planet II, we took a BBC team where no one had gone before: 1,000 meters beneath Antarctica’s ocean. This was unexplored territory that plays a central role in our planet’s life cycle. Called “the lungs of the deep,” it is the source of oxygen-rich waters that bring life to deep oceans all over the world yet there have never been manned submersible dives into these depths before. At 1,000 meters down, despite the extreme cold, we found a sea floor literally crawling with life and were able to study an ecosystem central to the planet’s lifecycle, producing oxygen-rich waters that flow throughout the world. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? MD: One of the things that surprised us was just the amount of life that was at the bottom. With such nutrient dense water we were able to find a much more vibrant sea bottom than what one might think in regards to Antarctica. One of the charismatic creatures we encountered was the Antarctic sunstar which we nicknamed the Death Star. It was absolutely massive with 50 arms that were raised into the air to catch krill as they passed by. It was a strange and wonderful world that was like taking a page from a Dr. Seuss book. What impact do you hope this film will have? MD: I hope to bring a much needed voice to the oceans in order to help galvanize the public’s interest in what lies below the surface by exciting, informing and inspiring audiences. With this film I hope to be able to open people's eyes that there is still so much more to be understood and explored in our oceans and that we have only scratched the surface. I think by combining charismatic science stories with the power of media it has the ability to proliferate, create conversation, inspire change and truly shift our culture. We have seen how media can shape the way people think, what they think about, and how they act which is why the work we do with OceanX is to help harness that transformative power in our efforts every day. I believe by invoking a human connection to the oceans, we can build a global community deeply engaged with understanding, enjoying and protecting them and I hope that this film will play a part in that. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. MD: There are definitely technical challenges that come into play - when we were in Antarctica, we had to make sure camera batteries didn't freeze and that our subs could handle the extreme cold. We’ve never had the submersibles in water that was so cold, and on one of our first dives, the camera teams and producers saw some condensation that was worrying—they didn’t know if it was a leak or if it was truly just condensation. Orla Doherty, one of the producers, was asked to taste it to see if it was salt water—then they’d know that it was a leak. She tasted it, and there was a leak. Luckily, they were able to bring the subs back up, check some of the valves, and fix the problem. But it was scary at the time. It was something we absolutely didn’t expect, given that we’d never filmed in super-cold water before. What drove you as a filmmaker to focus on our oceans and marine life? MD: Growing up near the coastline in CT, I developed a deep connection with the water. After studying film and working with National Geographic in L.A., I saw the unique need for and value in merging my two passions of filmmaking and ocean exploration, and wanted to create a media production company with the singular focus of exploring and broadcasting the story of our oceans for the world to consume. I founded OceanX Media with the mission to educate, inspire, excite and connect the world to the ocean through captivating media content and storytelling. Many people think that we know everything there is to know about the oceans, but in reality only about 5% of the oceans have been explored and documented. At OceanX, we are trying to bring a much needed voice to the oceans in order to help galvanize the public’s interest in what lies below the surface by exciting, informing and inspiring audiences utilizing captivating stories around the scientists that we work with.

0 Comments

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

My Octopus Teacher Trailer from Jackson Wild on Vimeo.

What inspired this story?

Producer Craig Foster: I have been diving in the kelp forest everyday for almost a decade now. I started because I was going through a very difficult time, but it became this incredible source of energy and inspiration. After almost 5 years I met a very unusual young octopus. I went back to visit her everyday for months and eventually the animal trusted me and allowed me to enter her secret world. I began to see her as my teacher because through her I learned to track underwater and discovered many animal behaviours and even species that were new to science. She also taught me about her many prey and predators and the inner life of the Great African Seaforest. I witnessed most of her life and managed to capture some of it on camera. For a time, she was the major focus of my life - I fell in love with her. I still regard that year with her as the greatest privilege of my life. When Pippa and I started going through the footage we realised we had something very special: a very personal, emotional story about an unusual animal/human relationship, but also the entire life story of an individual marine creature in the wild. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? CF: Any time you go into nature without a specific agenda, you find something meaningful and surprising. I spent hours and hours in the water with the octopus, but at the time I never had any intention of making a film, so everything I saw and learnt was a surprise and my understanding of the kelp forest expanded enormously because of that. At first I saw the Seaforest as thousands of separate creatures surviving and thriving. But over time, and especially when I was with her, I started to sense the entire Seaforest as a single living entity - a giant ecological intelligence. When you start to feel that and you start to feel that you are part of it, your relationship to the natural world changes on a physical and emotional level. I was always aware that we are damaging the ocean, but now it feels much more personal. By hurting nature we are hurting ourselves.

What impact do you hope this film will have?

Director Pippa Ehrlich: As filmmakers, we see ourselves as storytellers first, but when you spend thousands of hours in an environment and you start to fall in love with it, you reach a point where just sharing stories is not enough. I hope this film impacts viewers on two levels: first I hope it inspires them to explore the natural world in their own way. We are incredibly fortunate to have a seaforest on our doorstep, but I believe that it's possible to have a meaningful relationship with nature no matter where you are in the world, whether it’s with the insects in your garden, or a plant that you nurture in your apartment. Craig spent so much time with the Octopus that he got a glimpse of how she experienced life. It’s hard to articulate but there is something deeply fulfilling and reassuring about imagining the world through another species’s eyes. It expands your perspective. Secondly, we hope that our film has a tangible impact on ocean conservation and would like to be part of the global campaign to protect 30% of our oceans by 30/30. We know that marine protected areas are not a silver bullet, but there are still so many incredible wild places on our planet, if we can at least get the right legislation in place, they will become our ecological savings accounts for the future. On a more local scale, we are working towards having the kelp forest or “The Great African Seaforest” declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Describe some of the challenges faced.

PE: I have spent much of my career as a journalist, telling other people’s stories. In order to make this film, I needed to understand Craig’s experiences directly. Before we even started developing the script, I spent 6 months diving everyday to adapt my body to the cold and get confident enough to swim in big swell - not to mention that fact that this is one of the sharkiest bays on the planet. I also spent hours watching all of the different animals in the kelp forest and learning where to find them and how to approach them. One of the biggest challenges was learning how to find an octopus and it took months before I could recognise their tracks - even with Craig’s guidance. Those were very enjoyable challenges to overcome. The more difficult challenge was that in the beginning, this project was entirely self-funded. We knew we had an amazing story, but we also knew it would take a long time to get the cut right. We were taking a big risk and weren’t sure if we would ever be able to finish it. Fortunately, we had the support of Off the Fence. They really believed in the project and without them, we could never have got it to this point.

What drove you as a filmmaker?

CF: I have made a lot of films, but I have never told my own story before. There is something very powerful but also scary about doing that. My mother dived on the day I was born and I was put in the Atlantic Ocean when I was two days old. I started skin diving at 3, so my relationship with the Seaforest is one of the most precious things in my life. She has become my underwater home and I can’t imagine life without her. I wanted to share my experience with the Octopus and make a beautiful film, but more than that I wanted to honour this incredible environment because it has given me so much. My greatest wish is that this film can somehow inspire people to protect the Seaforest and the ocean that feeds it.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

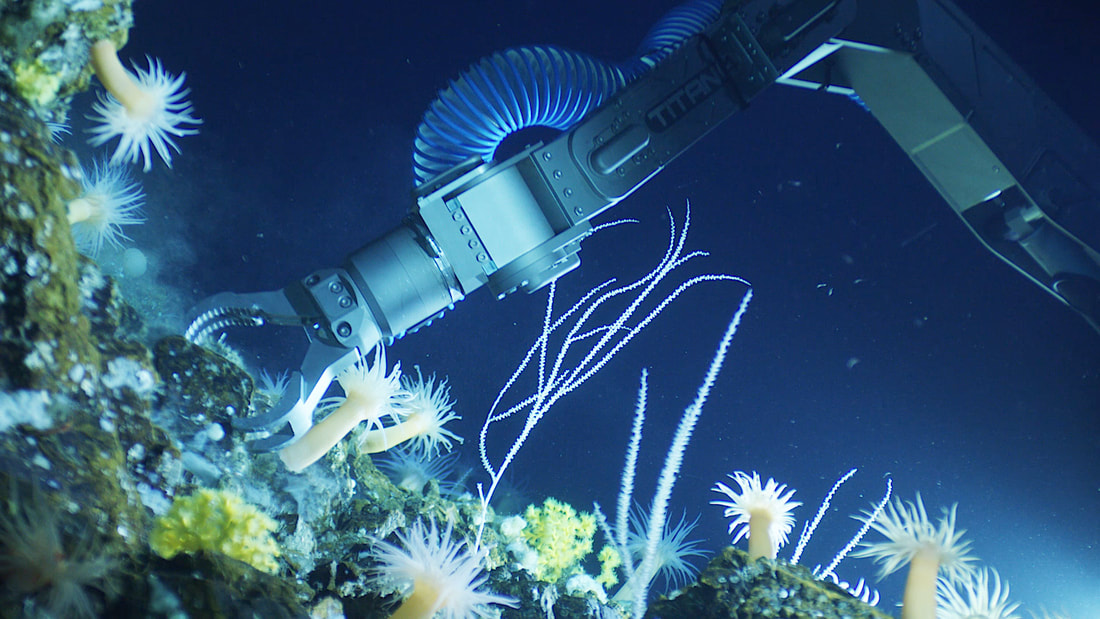

What inspired this story? Editor-in-Chief of bioGraphic and co-Executive Producer of the film Steven Bedard: We had an opportunity to join a deep-sea research expedition to an unexplored portion of the mid-Atlantic Ridge, following scientists as they probed the seafloor in search of signs of life thousands of feet beneath the surface. Their objective: to learn how life on Earth first began—and how it might evolve elsewhere in the Universe. As you might imagine, it was an opportunity we couldn’t pass up. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? SB: In the deep ocean, nearly everything is a surprise. So little is known about this part of our planet that scientists make new discoveries on practically every dive—previously unknown species, unexpected geologic formations, signs of life buried deep within solid rock. Many of these discoveries take place long after an expedition has been completed. Ask a deep-sea biogeochemist what she/he discovered on a recent trip, and they’ll almost surely tell you to check back in several months.

What impact do you hope this film will have?

SB: We hope that viewers will gain a greater appreciation for how little we currently know about our oceans—especially their deepest expanses—and how much these environments might teach us about the origins of life on Earth. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. SB: The extreme and isolated conditions in this environment—some of the same factors that brought the scientists to this location in the first place—posed many the greatest challenges to the researchers and our film crew. A spot in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, alongside a tiny, treeless archipelago more than a thousand kilometers off the coast of Brazil was the expedition’s home for more than two weeks. This would be a challenging location to mount a deep-sea expedition under the best of conditions, and these were not the best of conditions. Powerful currents and massive swells kept the research team’s submersibles onboard the ship for endless days. Finally, when the seas calmed the research team and ours scrambled to gather as much data and footage as possible. No one had ever seen this undersea terrain before, and there was no telling how long it might be before anyone would be back here again. What drove you as a filmmaker to focus on our oceans and marine life? SB: All clichés aside, it’s impossible to underestimate the significance of our oceans and the organisms that live there. Although we live on the terrestrial one-third of our planet, all of us depend on oceans—for food, for climate regulation, for the weather patterns they generate, and for the carbon dioxide they absorb. Yet, for all their value, we still know surprisingly little about many of these environments—how they function, what life forms they harbor, the threats they face, and the best ways to protect them for generations to come. We hope that films like these will help to illuminate these incredible places and the inspiring people working to understand and protect them. We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films. What inspired this story? Producer and Director Tom Mustill: In 2015 while kayaking with a friend in California I was breached onto and almost killed by a humpback whale. I became fascinated by these animals, and by the stories I started to hear about the whale-obsessed human community of Monterey Bay. When I learnt the grave problems the whales here face I became determined to make a film to bring these to people's attention. What impact do you hope this film will have? TM: We make films because we believe that doing justice to the stories we have heard will make people care and act. From the start our plan was to to effect people. In this film there are three strands - to entrance people with the wonder of whales, to shock them with the problems that they face, and to inspire them with the stories of people of different backgrounds making a difference as a community - people the viewers will hopefully feel compelled to support or emulate. Above all we want people watching to feel connected to the ocean, the animals in it and the people who love it. The production team and the people featured in the film have been overwhelmed with messages from viewers writing to say that they would like to become whale rescuers, vets, anatomists, scientists and whale watchers, and saying that as a result of the film they have volunteered to join a team, done a beach clean, donated already or wanting to know how to help. We are also aiming to show the film to key decision makers and to galvanise particularly engaged existing communities around new legislation particularly aimed at reducing entanglement and ship-strike and are already working with organisations planning work in this area to use the film in concert with their recommendations. We are proud that the film also shows a variety of impressive and highly competent people who happen to be women, and we have had very positive responses from our audiences regarding this too. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film: TM: Some of the filming was dangerous and sensitive - for example, being allowed along to film an active disentanglement required 6 months of careful negotiation with the US government and entanglement teams to get approval, which had never been granted before. Some of them were technical - to film the whale breaching at 1000fps (never achieved before) we worked with a camera inventor who'd managed to create a super high speed camera small enough that we could carry two with us at all times over months of filming, in case we got lucky with a breaching whale. But the greatest challenge was probably editorial. Storywise we wanted to try something quite difficult to do - to portray a community of many different individuals, within a television documentary. this was a tremendous challenge - to weave the location, all the different people, survivors of whale encounters, scientific history and new discoveries along with the dramatic whale deaths and rescues that we witnessed together, without it being a mess or people becoming overwhelmed or lost watching! We came up with narrative devices such as the stylised intros to contributors (and often their dogs) which would allow the audience to quickly get to know the characters and so remember them with a personal detail or two more easily than if they were just another scientist or whale watcher. We also used my personal near-death story to identify and find the whale that leapt onto me (which developed as a surprise during the filming - we didn't expect it to be such a success!) as first a hook to get as big an audience along for the ride as possible, and then interwove this through the film as a continuous strand linking the various contributors. Hopefully at the end this had the effect of starting with a small personal story and making you feel you'd got a handle on something much bigger and more profound.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story? Series Producer Mark Brownlow: The ocean is the most exciting place for us to be right now because scientific discoveries and new technologies have given us a completely fresh perspective on life beneath the waves. This series reveals new stories, featuring spectacular new places and extraordinary new animal behaviours that help us to better appreciate the wonder, magic and importance of the seas. It is amazing how much filming technology has moved on since the original Blue Planet series. We have harnessed new technology to tell stories - some never seen before - in completely new ways. Our underwater teams can now dive for much longer than conventional scuba ever allowed. Rebreather diving gives our teams time to sit silently and watch, with no bubbles or disturbance underwater, and really get to know new creatures and their behaviours. If you can sit in a submarine a kilometre down in the abyss for 1000 hours, as we’ve done, or stake out a coral reef with diving rebreathers; or with low light cameras reveal mobula rays in a surreal dance, illuminating worlds of bioluminescence and plankton, then you can tell certain stories that were off limits until now. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? MB: Over four years, we launched 125 separate filming expeditions across 39 countries, clocking up over 6000 hours underwater- and all the while sharing innumerable surprising and meaningful experiences with marine life. Here are just three stories from the field: Coral Reefs Stories: Grouper gesturing and hunting with octopus Coral grouper are some of the most common coral reef inhabitants and yet in the last ten years, research shows that their behaviour is so sophisticated that some aspects of their intelligence might rival that of chimpanzees. Groupers are mid water predators feeding on small coral reef fishes. They are fast in the open sea but too large to access prey in cracks and crevices. For this reason they seek out the assistance of a more manoeuvrable marine creature – a reef octopus. But what is truly amazing is that this is not simply a passive partnership - these animals communicate with each other. By assuming the headstand position and shaking their head from side to side above where a little fish is hiding, the grouper is able to tell the octopus where the prey is hidden. Gestures such as this are thought to only occur in the largest brained species and mean that fish are able to think flexibly to achieve their goals. Not only is this behaviour challenging our understanding of what a fish knows but it’s also making scientist rethink the definition of animal intelligence. Methane Volcano in the Deep episode: We set out to capture scenes at the extraordinary brine pool – an almost mythical lake at the bottom of the sea – and a death-trap to any unfortunate creature that strays into its toxic waters. For several days, we had been capturing wonderful footage of the scene that lay below us at the brine pool. But in the spirit of exploration, we ventured further west in the Gulf, to a site described to me by Dr Samantha Joye, our expedition scientist and deep sea researcher as a ‘thin curtain of bubbles’. When we dived there the next day, we found nothing but a barren desert when we first touched down. Then suddenly, just ahead of us, something shot out from the seabed. We watched it rise up into the water column – a huge bubble, the size of a basketball. As it ascended, a trail of sediment fell away from it, drifting back down. Then another bubble, and another. Suddenly, we were entirely surrounded by giant bubbles of methane, erupting from what had been an empty abyssal desert only minutes before. It felt as if we had voyaged to another planet and we nick-named the site ‘War of the Worlds’. We returned to ‘War of the Worlds’ twice more during our expedition. Both times, there was barely a puff coming from the methane volcano. We had been unbelievable lucky - the deep had given up one of its great secrets, but only the once. Giant Trevally sequence, One Ocean episode: A fish that launches itself, missile-like, to take birds from the air, sounded too extraordinary to be true. Despite it being a fisherman’s tale with no photographic evidence to back it up, I decided it was worth taking the greatest risk of my 20 year career. So 4 of us set off to a remote atoll on the Seychelles with 800kg of kit, including a stabilised camera, to film the action from a boat. Despite seeing splashes all around us from the start, the attacks on low-flying terns happened so quickly and randomly, it was almost impossible for cameraman Ted Giffords to frame up on the action. The unpredictability and constant drifting of the boat meant a frustrating week for Ted. But our Seychellois guide, Peter King, knew his trevallies well. He suggested that we go back on shore to a remote beach where for a few days each month the tides brought the trevallies close to shore. Here we had a much better view of the fish as they stalked the birds from underwater. Peter could even predict the ones most likely to attack. So despite all the expensive hi tech equipment, it was local knowledge that enabled us to turn the myth of a wild bird-eating fish into a reality. Finally we captured the moment the fish launches out of the water with phenomenal speed and acceleration and catches this bird in mid-air. And we filmed it in ultra-slow motion. To me it’s an iconic image, because in a moment, it transforms our understanding of what fish are capable of. I think that image alone speaks of the awesomeness, the power, the drama and the surprise that the ocean still delivers. What impact do you hope this film will have? MB: Blue Planet II was a box-office hit when it aired in the UK in Autumn 2017, drawing more than 20 million viewers to films about the open ocean, coral reefs and the deepest parts of our seas. The series has since televised around the globe – in the US, five times Emmy-nominated, it is the most watched nature program on US ad-supported TV in eight years. In China, it ‘broke the internet’ with audiences approaching a quarter of a billion. Globally, the series has set international audience viewing records for natural history programming, reaching half a billion people around the world to date. The series has not only broken the television box-office but has also drawn attention to critical issues such as ocean plastic, effecting change in both public opinion and government policy overnight. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. MB: The sea is a restless, ever changing environment; that’s part of its great appeal and mystery. But with that comes great challenges. Anyone who works with the ocean has to respect its capricious power. Filming underwater means being at the mercy of its great forces – tides, currents, winds, waves, crushing depths, poor visibility…can all make life extremely challenging. Those unpredictable elements, combined with the fact that we know less about the oceans than any other environment on Earth, means that underwater wildlife films are incredibly difficult to make. Our challenge too is to make people fall in love with less familiar animals and find personality in them. For instance, on the Great Barrier Reef we discovered that there is marine life like the tuskfish, octopus and coral grouper that are capable of behaviours so sophisticated, so smart, that scientists compare their behaviours to those of chimpanzees. Suddenly we’re realising there isn’t this vast difference between us and them. In the past, with other terrestrial wildlife series, the camera crew may have followed the studies of a particular scientist. They would have followed a scientist to a given location, set their tripod down with a long lens and sat and filmed the subject from afar. However, because of the practicalities of underwater filming, the cost of boats and the complexity of launching these really ambitious shoots to the far-and-beyond, a lot of scientists simply just don’t have that access. So, on this series, there’s been this wonderful synergy where we’ve been able to work with the scientists and contribute to their science through our filming. What drove you as a filmmaker to focus on our oceans and marine life? MB: I’ve had some great experiences during my four years series producing Blue Planet 2. From filming herring bait balls with orca and humpback whales in Arctic Norway, to diving into ‘the boiling seas’ off Costa Rica, it has all been an incredible privilege. But more importantly this is a once in a lifetime opportunity to introduce a new generation to the wonders of our ocean world. Blue Planet did an incredible job back in 2001, but with so many scientific discoveries in the oceans since then, along with advances in technology, we now possess a whole new understanding of life beneath the waves. In the four years of making this series, countless new scientific discoveries and papers have been published. With more people studying the oceans now than at any point in history, we understand both how the oceans work and our influence on them better than ever before. And that means we can portray a contemporary portrait of the world’s oceans – as they are today. What we reveal is sometimes shocking and even sad, creating a broader mix of emotions across the series. But perhaps the most exciting aspect of making this series has been that to best deliver new insights, we’ve not just been reporting the latest findings of marine biologists, we have joined forces with them, making discoveries together.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

Huntwatch Trailer from Jackson Wild on Vimeo. What inspired this story? Huntwatch Filmmaker: Thirteen years ago I saw my first seal hunt video - young seals, clubs and blood. It was too much for my soft heart. I avoided ever looking at this graphic footage again. Five years later, I was reintroduced while taking inventory of the film and video archives of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) in London and discovered a treasure trove. One film stood out called Sealsong. It featured IFAW founder Brian Davies sporting his aviator glasses flying helicopters, diving under the frozen ice and fighting the political system – all to save the baby harp seals from slaughter in Canada. Looking deeper there was even more - death threats, spy tactics, knife attacks and destroyed helicopters.A crusader for the seals, Davies devoted his life to end the hunt and I truly admire his courage and tenacity. The story captivated me and I needed to find a way to make a movie about it. This would be much more in depth than the simple documentary shorts I had made in the past – a feature. It would be a huge undertaking. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. The greatest challenge of filming Huntwatch was getting the imagery. The activists were trying to film seal hunting to make sure the hunters were following the rules, but the hunters didn’t want to be filmed. To capture footage our camera team had to endure incredible and dangerous challenges including hanging out of helicopters and using undercover spy cameras. They were attacked with a knife, endured a three day hostage situation, encountered dangerous weather, stood up to powerful politicians - all to save the seals. How do you approach storytelling? Some of our archive footage is incredibly disturbing, so we had to find a way to make the film watchable and entertaining to a broad audience. We worked very hard at finding lighter moments and human drama, trying to focus in on the characters to tell the story of their experiences around the seal hunt. The look of Huntwatch came about very organically. The footage has a natural progression through time and each generation of the Huntwatch looks very different. We wanted to keep the integrity of this look, so the 1970’s had a nice rich film quality, the 90’s had some rough chaotic video, and the modern hunt had the very crisp clean clinical feel of HD video. A major theme running through the film is that images and media were the weapons used to fight against the hunt. We tried to hint at this by using film imperfections, video glitches, and behind the scenes moments. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? Primarily an archive show spanning a full five decades, Huntwatch was not an easy film to tackle. People like the female lead, Sheryl Fink inspired me to stick with it. Tough as nails, she is the modern day Davies bravely monitoring and documenting the hunt from helicopters and ice pans, careful to not interfere. You can’t help but notice that this petite, young blonde is a bit like David versus Goliath. During our interview she said, “What are we going to do? They’ve got guns and hakapiks (clubs). We’ve got…video cameras.” Anything else you would like people to know? The Canadian seal hunt is a very complicated issue. Seal hunters are an easy target for blame, but the reality is that it is not that simple. Our goal was to tell an honest story bringing both sides of the debate to life as well as the political influences. This was a challenge because killing an animal naturally evokes heightened emotion. To counterbalance, we worked diligently to show the humanity of the hunters as much as possible. At the end of the day, they are just guys doing their job.

What do you see as the impact of the individual, group or movement featured in the film? What real tangible impact do you hope to achieve?

Four million seals have been saved since the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) had their first big win for seals with a European ban on newborn harp seal products in 1983, which shut down the hunt for several years. In more recent time, animal activists achieved another win in 2009 with a new and improved seal product ban in all EU countries, but this time it prohibits the trade of any seal regardless of their age or species. This was a huge victory for seals and slowed down the hunt considerably from 355,000 seals killed in 2006 to 76,000 in 2009. Although seal quotas remain in the 400,000 range – far fewer seals were killed in the commercial hunt last year and each pelt is valued at only about $25 compared to a few hundred dollars in the hay day. The number of sealers is dropping too from 6,000 in 2006 to only 400 today. Government subsidies keep the hunt alive and ironically these hand-outs actually outweigh the profit generated from selling seal products. In fact, the CA government provided more than $20 million from 1996 to 2001. The good news is that those numbers are decreasing, but without a complete end to this funding; the hunt will continue.Eighty thousand people have already joined IFAW, signing a petition to Prime Minister Trudeau to stop the subsidies, buy out the sealer’s licenses and invest in other industries. Across Canada most people actually oppose the commercial seal hunt. Sealing has been enmeshed in the culture in Atlantic Canada and people have been afraid to speak out on such a heated issue. Lead Huntwatch character Sheryl Fink is taking a grassroots approach and has formed relationships with a few hundred concerned citizens in sealing communities, screening Huntwatch to enthusiastic audiences and gathering petition signatures. Highlighting the untold story of one of the most important animal welfare issues of our time, Huntwatch is sure to make a big impact on everyone who sees it. And once they realize that baby seals are still being killed, they will join Sheryl Fink, sign the petition to end government subsidies and relegate the hunt to the history books. Thirty-five countries around the world now have seal bans in place and now we just need one more. We are making progress. The film has been publicized as a “Must See” movie by critics at both Indiewire and the Santa Barbara Independent. Canadian born narrator and Hollywood star, Ryan Reynolds grabbed headlines like, “Ryan Reynolds is Using his Voice to Help Save Baby Seals” and “7 Pic Pairs That Prove Ryan Reynolds and Baby Seals are a Match Made in Heaven.” It showed at festivals throughout the U.S. to engaged audiences, who want to do their part to help. The incredible attention of Discovery and Lionsgate is bringing Huntwatch to vast audiences and creating a ground swelling of support, which will end the hunt once and for all.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Producer Annie Moir: I studied marine biology at university and for my dissertation I looked at how we could possibly break down humpback acoustics and taking into account behavior and anatomy, look at patterns within their song and form a language. An area I touched on in this study was how noise pollution in the oceans affects their acoustics. I was shocked and felt I must do something. To think there is something that is stopping the most beautiful (to me) natural calls and sounds in nature was baffling. Whenever I spoke about noise pollution to anyone the immediate and consistent response was, “I never even thought about the noise we make and how it could affect them, but it makes total sense” So, to me, it made total sense, to make a film about this issue to try and increase the conversation and hopefully shed some light on a topic which is often ignored. Finally, where plastic pollution often feels like a huge struggle we may never fix, I find noise pollution a much less daunting problem that we as a species face. The fact, as the film touches on, that noise pollution could be gone in 18 hours and with no lasting effects, really empowers me and hopefully the audience into wanted to be active and make a difference now. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? Director of Photography and Aerial Camera Operator Michael Clark: We had nine days in Iceland on the water to shoot this film, and only one day to rent out one of the small rubber dinghies that would allow us to get closer to the whales. Lucky for us, the day we rented the dinghy was the greatest weather window we would have on the trip. After hours of chasing whales, finding a blue whale, and chasing humpback fin slaps and breaches, we were met with one of the sunsets that last for hours due to our proximity to the arctic circle. When the sun started to go down, the sea glassed over, and the whales began coming so close that my zoom lens couldn’t focus, I couldn’t believe our luck. I watched whales dance beneath our tiny boat, repeatedly felt the salty breath of humpbacks on my face, and destroyed a $2k camera to never come back to life. Yet, I could have never imagined the excitement I felt. For the first time in my life, even with having worked with whales quite a bit, I began to understand the titanic reality, grace, and intelligence of cetaceans. I came away from Iceland with the understanding I needed to alter my life path and dedicate myself to wildlife conservation. This day will always be remembered as a turning point for me, and my career. AM: I second everything Michael says here, that was a magical day filming and to see humpbacks lunge-feeding around us, after studying them for so long (AND TO FILM IT), was the best experience of my life! What impact do you hope this film will have? MC: Noise pollution is an issue that is rarely talked about in our society and is something that is can often be overlooked by conservationists. While we hope the film will ultimately impact the way consumers approach their spending habits or to increase legislation to reduce noise pollution in its various forms, even to just leave a lasting impression of the beauty of the humpbacks or add to the conservation conversation would be an incredible blessing. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. MC: Shooting on the water 50 miles south of the Arctic Circle certainly has its challenges. Mostly in the form of unpredictable weather patterns. Consequently, perhaps the greatest challenge was employing trial and error to find the correct time, and use the correct systems that allowed us to shoot stable shots on the rolling sea. As a very low-budget film, we couldn’t afford the long lens gimbal systems that could solve this issue, so day after day the team discussed how we could alter the way we were approaching the day’s filming to counteract these diverse, windy, and swell dependent shooting days. Further, flying drones from boats is an intense challenge that resulted in us wrecking our drone 5 days into shooting. Luckily, North Sailing (the whale watching company we partnered with to have access to these whales) had a drone that we could use. The day they gave us their drone was the day where we filmed 90% of the drone footage of whales in the film, and captured what I believe to be some of the most impactful shots. AM: For me, the hardest part had to be finding the right way to tell the story and issue of noise pollution and do justice to this incredibly direct and damaging pollutant. It was a topic that needed a different approach of filmmaking to ensure it reached as many people as possible, mainly because we as a species, cannot even begin to understand as we do not communicate underwater and cannot hear the problem clearly ourselves. Hopefully, to overcome this, the immersive nature of the film and the cymatics, encourages the audience to feel the issue of noise pollution instead of telling them about it. What drove you as a filmmaker to focus on our oceans and marine life? AM: I grew up as far from the ocean in the UK as possible. But sailing throughout childhood allowed me to discover my passion for being on the oceans. Then mixed with a combination of loving the film Jaws and watching David Attenborough’s Blue Planet, I knew I wanted to study marine biology and then communicate this new-found knowledge and my experiences through making films and taking that information home to friends and family in Leicester, who may not have the same opportunities. I want to develop a bridge between science and communities of people who have the power to make a difference through small behavior changes, through making films and communicating the issues our natural world faces in the most effective way possible. MC: It was my first experiences of working with cetaceans in New Zealand that really sparked the drive to focus on marine mammals and ocean conservation. Spending six months in Auckland as the head of video media production for Auckland Whale and Dolphin Safari really gave me insight into the conservation challenges and fragility of these ecosystems, but also allowed me to gain a deep appreciation for the intelligence, social structures, and charisma of these animals. When I was given the opportunity to work on A Voice Above Nature with Annie Moir, I jumped at the ability to create work that directly spoke to these conservation challenges and issues.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Producer, Camera Operator, Narrator and Editor Tom Parry: Like a lot of us, I have two sides to my personality - an artistic side and a scientific side - which I’ve struggled to reconcile throughout my life. After spending most of my school years aspiring to be an artist and building a portfolio of work, in 2013 I changed course and went to University to study Zoology. Over the next few years I worked with wildlife biologists around the world and developed a strong appreciation for the incredible intricacy and vulnerability of nature. I also came to realise that - contrary to the narrative I was given at school - science and art are not mutually exclusive. Science has room for creativity, just as art has room for objectivity. I want to share my passion for wildlife and engage people with the natural world. A Place For Penguins is my first venture into filmmaking. I researched, filmed, edited and narrated the film for the dissertation of my recently completed Masters in Wildlife Filmmaking at the University Of The West Of England. My aim was to tell a story that demonstrates the inherent compatibility of science and art. Conservation is a collaborative effort and I believe that if we are going to meet the challenges facing our planet we need to cooperate, think outside-the-box and break down traditional academic disciplines to unearth innovative solutions. So A Place For Penguins is a story of conservation, creativity and collaboration.

Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share?

TP: I was very surprised when I first saw the POV footage taken from on-board cameras strapped to the penguins. We tend to think of penguins as somewhat silly creatures – there’s no getting around it, when they’re on land they’re hopeless. It’s a huge part of their charm. Sat behind the lens, I found myself laughing out loud at the things as they struggled to waddle up the shore. But their agility on land is hampered for a reason – under the waves that body shape makes complete sense. It’s incredible how nimble and agile they are, and the speeds they can reach at full pelt isn’t half bad – over 20mph. I was really pleased to be able to include those shots in this story. I think perhaps we spend a little too much time laughing at penguins. It’s good see them in their element and appreciate them as the proficient marine predators they undoubtedly are. Another surprise, I wasn’t quite ready for the smell of full penguin colony...

What impact do you hope this film will have?

TP: When I told friends and family of my plans for this film, the most common response was “Penguins? In Africa? What are they doing there?” Most people didn’t realise penguins are native to the continent, let alone that Africa has lost 99% of them in the last 100 years. This ignorance isn’t confined to London – even in Cape Town, the penguins’ perilous situation did not appear to be common knowledge. Locals would often recommend the penguins to me as a tourist activity, then be shocked to be told that I was there as a filmmaker to document a desperate rescue mission for them. I hope that this film does a little to highlight the effects the industrial fishing industry is having on Africa’s few remaining penguins, a species that is so often overshadowed by Africa’s more stereotypical wildlife. On another note, I also hope that Christina and Roelf’s story will challenge a traditional narrative that I have a personal gripe with - I dislike the idea that creative and artistic people have no part to play in science. Christina’s willingness to think outside the box and take a huge, daunting challenge head on is truly inspiring, as is Roelf’s new outlook on his work and the role he can play in conservation through his art. Everyone has a part to play in preserving our natural world and I hope through seeing this film others have the opportunity to be inspired by Christina and Roelf, just as I was.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

TP: As a recent Biology graduate, this was the first film I have ever produced. Almost everything was new and everything a challenge! Overall the experience has given me a massive appreciation for the vast array of technical skills involved in a production like this. From shooting to sound-recording, mixing to colour-grading, the number of individual specialist skills involved is huge. Travelling to Cape Town for the first time alone to film and taking on almost every role in production myself has been a very humbling experience which has given me yet more admiration for the skill and dedication of those filmmakers I’ve drawn inspiration from over the years. I’m honoured to be shortlisted alongside some of them in this festival. I found keeping the film short a huge challenge because I encountered so many people with great stories to tell about Africa’s penguins. I had to let go of a lot of footage I wanted to include. Also, making this film as a self-funded student, I struggled to get to Africa in the first place – I was only able to do so due to the generous backing of my crowdfunding project. I’m very grateful to everyone who contributed.

What drove you as a filmmaker to focus on our oceans and marine life?

TP: The oceans have always intrigued me. Given how much of our planet is covered with water, I find it incredible how little we know about them. Historically even the most renowned environmental thinkers saw the oceans as an untouchable, endless resource, ‘limitless and immortal,’ which our species could never significantly impact. We’ve now begun to realize just how wrong they were. Our capacity to disrupt entire marine ecosystems is being demonstrated to us before our very eyes. And the plight of these penguins perfectly demonstrates that this damage is not confined to beneath the waves. The effects of overfishing, pollution and global climate change will be felt not just by marine life, but all those familiar animals we know and love who, just like us, depend on healthy oceans for their survival. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

Contact UsJackson Wild

240 S. Glenwood, Suite 102 PO Box 3940 Jackson, WY 83001 307-200-3286 info@jacksonwild.org |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed