|

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Director Cepa Giblin: It was the long term ambition of Producer and Director John Murray to make Wild Ireland. There have been many, many films made about the West Coast of Ireland but he felt none of them did the place the justice it deserved. For various other productions he had travelled the west coast extensively and always felt there was an atmosphere and a magic to the place that was never quite captured. So it was with this ambition that he set out to make Wild Ireland. To reveal Ireland, and specifically the west coast, in the way that he had experienced it. To try and give the audience a taste of the mood and beauty that the coast has to offer.

Question specific to category: Host/Presenter Led

Why did you pick Colin Stafford-Johnson to be the on camera host telling this story? CG: There was really no choice to be made. We had worked with Colin for a number of years on a number of productions and he was the natural fit for the series. Having travelled the world making natural history films for many years, Colin finally settled on the West of Ireland as his home. While we wanted to make a film that captured our beloved West Coast, Colin wanted to discover this place that he had been drawn to, so we felt combining the two was the logical thing to do. Colin has a unique style of presenting that brings the viewer on a very personal and passionate journey and we felt his style of presenting would be key in bringing the charm of the location to life.

What Next?

CG: For the last 10 years we have primarily focused our natural history films in Ireland. The notorious Irish weather finally broke us during Wild Ireland and we decided that next time, we needed some tropical beaches and sunshine. So, our next project is on the natural history of Cuba. What impact do you hope this film will have? CG: The big hope for this film was that people might take a closer look at their home turf and see how much there is to value in it. We are constantly looking abroad, ignoring what we have in the hope of having a 'wild experience’. Wildness is elsewhere, not next door. We wanted to convey the idea of just experiencing wild places, not necessarily having to witness major natural events. To show the value of just getting away, getting out on your own and taking it all in. However, during broadcast a panic did strike us as tweets rolled in asking the names and locations of places…...…the dread of these places been flooded with people and us being the cause.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film?

CG: There were two major challenged in making this series. 1. The weather - we all know Irish weather is appalling but we weren’t quite prepared for what the gods would throw at us over the three years of production. The first two years were 2 of the wettest years on record in Ireland and with very poor sea conditions. Luckily our prayers were answered for year three, when it all came together. 2. The second challenge was trying to find new ways to tell very familiar stories. Ireland’s wildlife is not unusual and most of the animals have featured in numerous documentaries over the years. There was a feeling that people had seen it all before, we were retreading old ground. So, we were constantly trying to look at new angles on their story, trying to highlight the smaller details that might usually go unnoticed - for example the affectionate cooing and preening of the Manx Shearwaters after been apart for days or the retreat of the defeated Red Deer stag into the woodland to die. We were trying to bring to the fore the emotion in the stories of the animals, to make the audience connect with them in a different way.

0 Comments

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Producer and Director Jeremy Monroe, Freshwaters Illustrated: I learned about the ecology these amazing river shrimp as a graduate student studying aquatic ecology, and since making the transition into filmmaking, I've always wanted to produce a film about how these unseen communities contribute to the delivery of clean water. Our partnerships with aquatic scientists at the Luquillo Long Term Ecological Research station and the US Forest Service are what finally allowed us to pursue this story. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. JM: Capturing the natural history for this film took weeks of filming over multiple trips. In addition to heavy rains and high river flows that would prevent underwater filming, these streams are some of the most steep, rugged, and slippery we have ever filmed in, and luckily, we didn't hurt ourselves!

How do you approach storytelling?

JM: We focus on immersive documentary films in freshwater ecosystems, so we start with a freshwater place, species/community, or conservation angle, and look for strong, passionate voices that can speak to those, and then we look for the visual narrative that can reveal it. We're always trying to take people underwater in fun and unexpected ways. What impact do you hope this film will have? JM: We hope this film will help shine light on river ecosystems and their values in Puerto Rico and throughout tropical Latin America, and especially the need to maintain the migration connectivity of rivers in this region where many dam projects are currently being developed.

What next?

JM: There are many, many more fascinating stories to share in the world of rivers and freshwater ecosystems. Our organization, Freshwaters Illustrated, is focused on telling these stories, and we have several projects in the works, including a forthcoming feature film on the diverse fish and aquatic wildlife of America's Southern Appalachian mountains.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Co-Director and Producer Susan Todd: Our micro-movie grew out of our experiences and observations in the woods around our backyard in Westchester, NY. We’ve lived in the same place for two decades, and we’ve spent a lot of time with our kids making gardens and exploring the ponds, wetlands, and forest. The spring migration of the spotted salamander and all the other miracles of nature became the subject matter that we wove into this story. As filmmakers, the need to reconnect to our environment is something we felt an urgency to communicate because it’s critical for children to get off their screens and get outside more. Our micro-movie is an introduction to a Giant Screen/IMAX film project and educational outreach called Backyard Wilderness. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. ST: Working in snow and freezing temperatures, filming at night, in the rain, 70 feet up in trees, and waist deep in vernal pools; these were some of the challenges of filming this movie. Perhaps the most challenging thing of all was working with the timing of animal births, like the hatching of the wood ducklings. We had to be very patient and calculate gestation periods.

How do you approach storytelling?

ST: We tend to work in two directions. With the animal sequences, we go after the natural behaviors we’ve researched that make for the most drama and important science and ecological impact. For the narrative arc of the story, we wrote a script that incorporates these sequences into the activities of the human family living in their midst. What impact do you hope this film will have? ST: We hope this film will help launch a campaign to get kids to put down their screens and get outside to appreciate the nature around them. There has been a huge increase in obesity, depression, diagnoses of ADHD, and there is clinical evidence that increased exposure to nature actually reduces these problems and helps people heal. We’ve been developing a multi-platform educational outreach and collaborating with other not for profits as a way of expanding our message.

Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share?

ST: The footage in this micro-movie spanned three years and during that time we observed that the Spring seasonal migration of the salamanders and the wood frog breeding came earlier each year. It gave us pause thinking about climate change and the impact our human presence was having on this ecosystem. Anything else you would like people to know? ST: The human family in the movie is actually our family and its our home. Andy and I play the parents in the film and we are very grateful to our kids (Walker, 17, and Clara, 12) for participating in this movie as actors, and having the patience to deal with camera crews in the kitchen!

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

The immense size and scale of China and its vast diversity of wildlife...imagine following the lives of several iconic Chinese animals as they each give birth. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. We faced a huge array of challenges – from working with a Chinese director with little personal experience or knowledge of wildlife…to getting permits to film rare animals in an array of impenetrable habitats…to producing our first feature film in a foreign language! A long list of unprecedented challenges for us.

How do you approach storytelling?

Always: chose your subject carefully. Do your research thoroughly. Chose the best cameramen to film your story… Watch what happens! What impact do you hope this film will have? We hope that Born in China will inspire the Chinese people to love and respect their wildlife enough to protect it.

Anything else you would like people to know?

We were honored to work with some of the world’s best cameramen, including Shane Moore (from Jackson, Wyoming) who faced the enormous challenge of filming an elusive and magical cat – (the snow leopard) - in a vast mountain-scape… A feline needle in a Himalayan-sized haystack. Would he find the snow leopards, let alone be able to film them? In the end, we managed to obtain the very first images of a snow leopard family in its natural setting. What next? We’d love to film another Disneynature story!

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

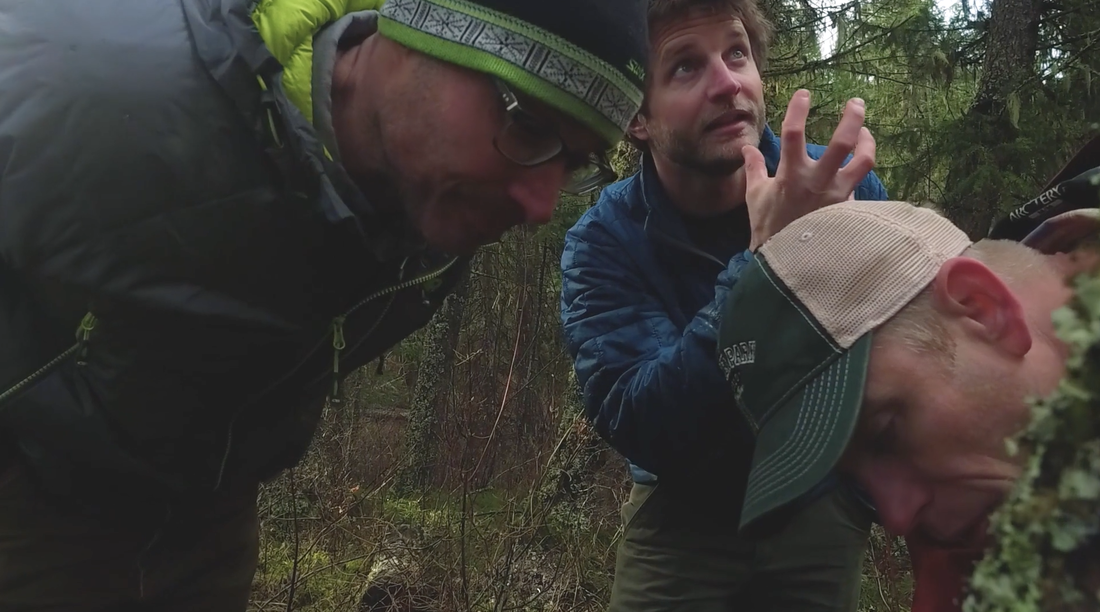

We made this film as a part of a new filmmaking workshop sponsored by the International Wildlife Film Festival, called IWFF Labs, with Days Edge Productions. The group selected for this workshop comprised biologists, filmmakers, and journalists. We were formed into 4-person groups with mixed expertise, and paired with a scientist local to the University of Montana. Then we had half a day to plan, 1.5 days to shoot, and 2 days to edit this film. We had to quickly adapt to a new group dynamic, delegate and prioritize tasks, divide and conquer. The scientific discovery was deceptively simple: 3 symbiotic partners in lichen instead of 2. But because we were excited and immersed in the science, we wanted to add in a lot of details about the scientific methods that completely muddled the story. We had to overcome our interest in the details to tell the larger story. How do you approach storytelling? Our team is diverse in its approach to storytelling, however, one common theme was humanizing science. We filmed the scientists in the woods and in their homes, so we could convey a human story of discovery. We wanted our main characters to be scientists, as the relatable people they are, outside of the categorical nerd or professor role. We loved telling this story about people and lichens in the woods, with all of the magic found in sunrises, cabins, and dewy trees.

What impact do you hope this film will have?

The scientists didn't want the story to be about them, but rather about the process of discovery. We decided to focus on the idea that a world-wide group of scientists helped each other question their assumptions to make this discovery. Through teamwork, persistence, and creativity, they discovered something incredibly important about organisms that they see every day. Hopefully young scientists will see this film and feel emboldened to question the status quo and seek out symbiotic collaborations. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? At one point, we wanted to make an analogy of a lichen, by showing all the different components on a pizza: basidiomycetes represented by chanterelles, ascomycetes represented by morels, and algae represented by nori. Tim, whose cabin we shot at, ended up having all of these components, and they made mushroom-related food for us whenever they weren't on camera. Mushroom omelettes for breakfast, mushroom pizza for lunch, etc. Even though we didn't end up using the analogy, we felt like we were becoming one with the fungi.

Anything else you would like people to know?

Lichen scientists are incredibly lichen-able! We lichened hanging out with them while making this story. They really are a bunch of fun-guys. Not mushroom to discuss more. What next? We are hoping to tell more stories with John McCutcheon’s lab. Stay tuned! What inspired you to tell this particular story? What did you learn during the making of this film? We were inspired by the collaborative scientists studying symbiosis. We learned so much doing this, really. It was part of a course that taught some of us more technical skills, while others more storytelling. We learned from each other mostly, each person pitching in with their expertise and helping others with less experience. Any surprises? Lichens are charismatic! Lich, who knew?

How do you foresee this nomination impacting the life of your film and your career as a filmmaker?

Kate - Confirmation that we have the skills we need moving forward. I am transitioning to full time science media, and this nomination is an important, well timed confidence booster. Talia - This nomination has opened my eyes to the huge impact a short film can have. I am currently applying for professorships and plan to incorporate outreach filmmaking into my research program, especially since my biomechanical studies involve lots of high-speed video. Chris - This film was an exploration into the minute and often overlooked world of lichens. Having the film nominated was a wonderful reassurance that the little things in nature can also share a spot in the wildlife media limelight. I hope this film becomes part of a growing body of high quality media that showcases the "smaller majority." Now, more than ever, I'm looking forward to watching that growth and being a part of it myself! Andy - For me, it was thrilling to get to meet and work with these other young, excited filmmakers and scientists. To have the fruit of that whirlwind effort invited to screen at Jackson Hole is a real inspiration to continue these kinds of collaborations with peers in this amazing world of science and natural history film.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

How do you approach storytelling?

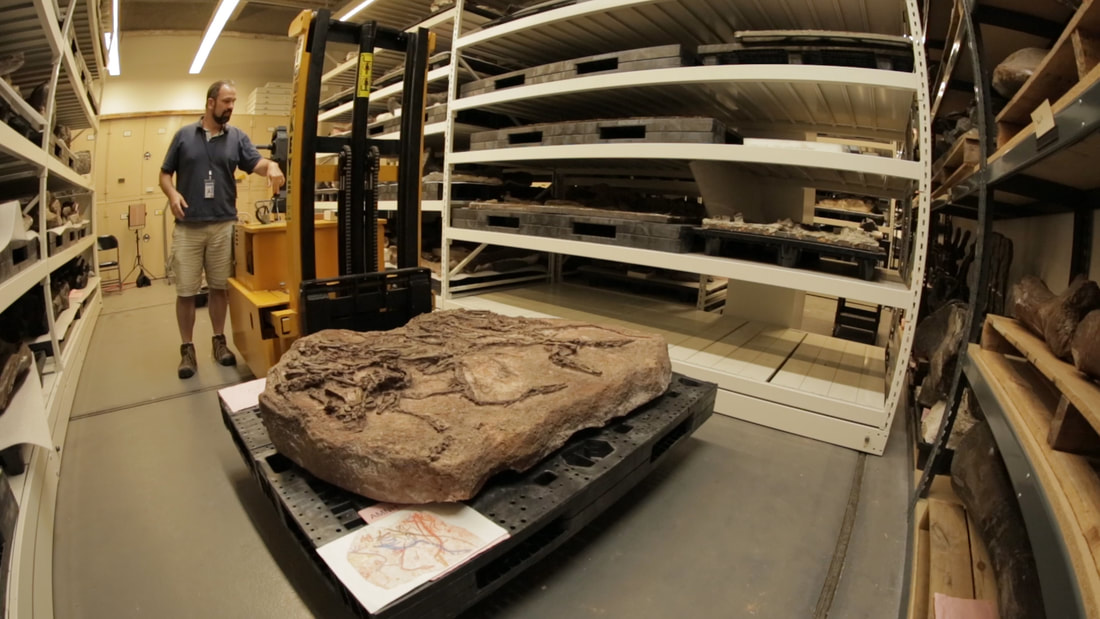

Creator and Producer Erin Champman: Unlike many of our adventurous colleagues at Jackson Hole, the Shelf Life team rarely leaves the four square blocks of Upper West Side Manhattan that make up the American Museum of Natural History. When producing episodes, we look for the exciting stories and personalities in our own backyard—stories based here, but far-reaching in their scope. This process involves lots of one-on-one conversations, plenty of reading, and hours of detective work inside the Museum’s archives and scientific collections. Conversations with researchers often lead to big picture ideas we then explore through the lens of a particular narrative. For example, in the tale of our giant squid’s journey to New York, we interwove the concept of how scientific taxonomy changes over time. To support these themes and stories, we find charismatic ambassadors amongst our staff and researchers, and look for ways to share their stories with creativity and a bit of fun. We aim to combine rigorous scientific filmmaking with imagination and humor.

What impact do you hope this series will have?

EC: In the course of filming, our Ichthyology Curator Melanie Stiassny told me, “Look, even if I had all the money in the world, even if I could travel to every corner of the globe, I could never reproduce what we’ve got here [in the collections] because the world has changed.” That’s a powerful statement. The collections at the American Museum of Natural History (and other museums around the world) are simply irreplaceable. They’re a time capsule of life, teaching us about its history and our future. One of the most important missions at the Museum is active scientific research, and one of its greatest scientific resources is its world-class scientific collection of more than 34 million specimens and artifacts. We want to upend the perception of museums as simply storehouses for big bones gathering dust. Instead, we want our audience to see natural history collections as dynamic places of discovery where new species are revealed, surprising relationships come to light, and researchers learn new questions to ask. I also hope to convey a message of inclusive science. We try to mirror who we want our audience to be by highlighting diverse voices from around the Museum. Ideally, some of those voices would inspire viewers to maintain a lifelong interest in science, or even to become a scientist themselves.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

EC: For our Shelf Life episodes, we can’t simply film specimens in a cabinet. Each episode forces us to come up with a new way to tell the story of a museum collection. For some projects, this involves spending hours in the Museum’s archives—deciphering 19th-century handwriting scribbled in the rainforest, or scanning thousands of expedition photographs to find just the perfect shot. For others, we’ve had to creatively visualize unseen phenomena or unknown organisms—how do you show the application of gene sequencing techniques to historical linguistics or evoke an organism known from a single tooth—all while maintaining scientific rigor. Those kind of challenges stretch our imaginations and are some of the many reasons we love producing this series. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? EC: We’ve been pleasantly surprised to hear that Shelf Life has actually inspired some scientific inquiry and collaboration. It’s exciting to have the general public watch our series, but there’s an extra thrill knowing that researchers also have an eye on the videos. In one instance, a cell biologist saw our video on salamander-algae symbiosis and contacted our curator with information about what may be a related type of relationship in other organisms.

What next?

EC: We’ve entered our second season of Shelf Life and have been excited about our new slate. Our first set of 12 episodes was a kind of Museum Collections 101, exploring fundamental ideas about organization, preservation, technology, and the importance of historical specimens to current research. In our second season, we’ve been expanding on those ideas, and linking each episode to a particular expedition from the American Museum of Natural History. These expeditions—from 1920s paleontological digs in the Gobi Desert to 21st-century collaborative research in Cuba—take our viewers along on a specimen’s journey from field to lab, and the science that happens along the way. As a part of this new slate, we’ve begun producing 360 videos (one of which is a finalist in the VR category) that aim to embed our audience inside historic expeditions. It’s a whole new way of bringing archival materials to life, and we’re looking forward to continued innovation in the 360 medium.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Director, Writer and Photographer Richard Ladkani: The idea came from an article in the New York Times, that Richard Ladkani read in early 2013, about the possible extinction of elephants within ten years. It was unbelievable to him that neither he nor anybody he consecutively asked about it, had ever heard about this problem. Something had to be done to raise awareness and what filmmakers can do is make a film with the hopes of having an impact. He teamed up with his good friend and colleague Kief Davidson as co-director and they pitched the film to Terra Mater Factual Studios, as well as Vulcan Productions, who both agreed to produce it. The goal from the beginning was to make a film for the widest possible audience, have a global reach and try to pressure China to ban the trade in ivory. All of us were very focused on those goals and gave our everything to achieve what we set out to do.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

RL: The biggest challenge on this film was to keep up with our characters without interfering in their work. This was one of the mandatory requirements they gave us, to never hold them back. There could never be any repeats, everything needed to be captured as it happened with no second chances. It took an immense effort to stick to those rules but this type of approach also had a very positive impact on the look’n feel of the film. With a camera always hovering around, we were able to capture very special moments of emotion, danger and success that ultimately contributed to the success of the film and its impact around the world. Questions for Specific Categories: Impact What do you see as the impact of the individual, group or movement featured in the film? What real tangible impact do you hope to achieve? RL: We wanted to create a film for the widest possible audience, which was one of the reasons we chose a very thriller like approach when making the film. Our audiences should feel embedded with our characters and experience first hand, what it must be like to try to save a species from possible extinction. With over 100 million subscribers, Netflix was also part of the impact strategy as we wanted to reach a vast global audience upon release of the film. When China declared to ban the ivory trade only two months after our global launch date, we really felt empowered, especially as we were invited to open the film at the Beijing Int. Film Festival only two days after the announcement was made and later won the top award for best documentary feature. Even if our film only had a fraction of an influence for this ban to be put into place, it shows that films can make a difference and that it is worth fighting for what you believe in.

Editing

What tone did you try to capture through the editing this program? Editor Verena Schoenauer: For editing "THE IVORY GAME“ the main goal was to show the urgency of the poaching crisis, which seems so far away for most of us, and give it a face. Getting as close as possible to those people, who fight and risk their lives everyday for the survival of elephants, and telling these scenes in a very rough style renouncing any mitigating details shows this cruel undercover war in all its brutality. It was a thin line to not leave the audience behind completely hopeless and desperate. Creating a sense for the elephants as intelligent individuals with very different characters was essential to make the audience understand what we are about to loose and that it is worth fighting for the survival of these magnificent animals. Besides unveiling the ruthlessness of the ivory trade as an international crime, the emotional approach was always an important factor. Only if people understand – not only intellectually but emotionally – what we are about to loose, they will support those people in the front-line who cannot win this fight alone. Because you only fight for what you love.

Writing

What were the biggest influences on how you approached writing this project? RL: Our characters really believed to fight for a higher cause and we wanted our audiences to share that feeling with them. We chose to write a Jason Born type eco-thriller that evokes a feeling of immediacy, of being in the middle of the action at all times. We wanted to create some sort of reality you rarely see on the big screen. Nothing in our film was scripted and yet when we wrote it, we envisioned our film to play out exactly as it ultimately did. With some exceptions of course: Nobody could have anticipated that the largest poacher in East Africa aka “the Devil" would ultimately be caught on camera or that Kenya’s stockpiles would ultimately be burned. This was wishful thinking but quite a pleasant surprise when it became true. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

Contact UsJackson Wild

240 S. Glenwood, Suite 102 PO Box 3940 Jackson, WY 83001 307-200-3286 info@jacksonwild.org |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed