|

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired the story?

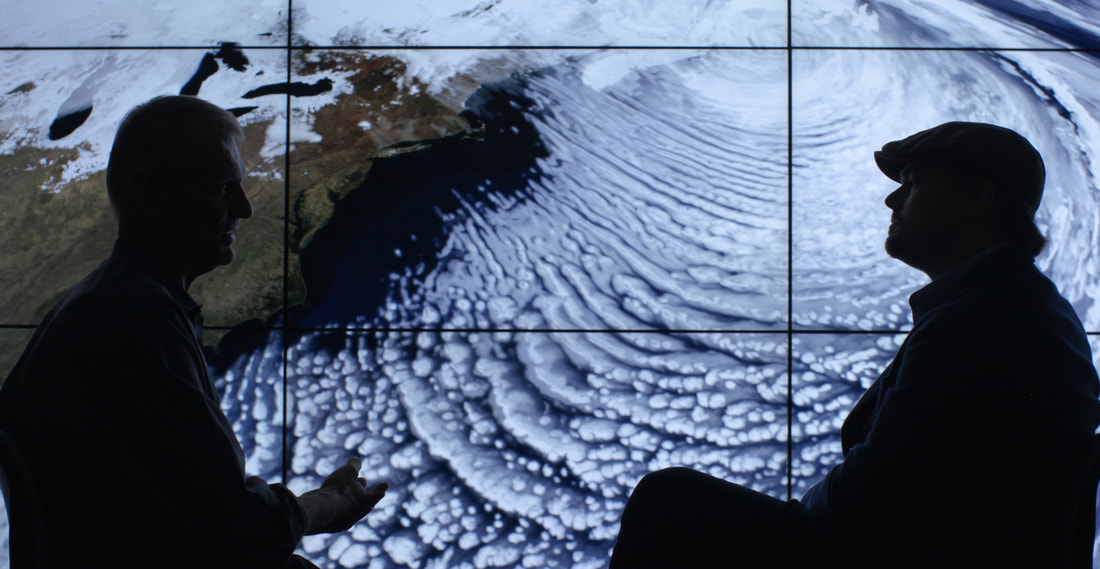

Director Fisher Stevens: Leo and I have known each other for many years and were both impressed by each other's efforts and curiosity in environmental issues. We both questioned how in this day in age, and from what science tells us, and we have all seen, how this issue is still one that is often debated. We realized the importance of going on this journey and really seeing first hand what the impacts of climate change are, and understood the importance of making a film that was emotional and impactful. That we couldn’t just do the usual doom and gloom type of film. This is an issue that is overwhelming for many to understand. We wanted to try and find a way to make and important and entertaining film that would really galvanize people to want to take action. We agreed that having Leo in the film would be essential and hopefully find an audience that wouldn't normally watch a film about climate change. Describe challenges faced when making the film. FS: It is a hard topic, people's eyes can glaze over once you start speaking about climate related issues. It is a massive subject that can take a filmmaker into a million different directions. We met so many incredible characters doing important work that it was challenging and painful to have to cut certain scenes and people out. Another huge challenge was to figure out how to make these scenes digestible and relatable for an audience.

How do you approach storytelling?

FS: For me, storytelling is all about characters and a journey. It has to be emotional. This is why we realized the importance of making this a film about Leo’s journey as well. What impact do you hope this film will have? FS: We wanted first and foremost to make people aware of the importance of this issue and that there is a ticking clock. To try to get people to understand that we all have to think differently about their everyday actions and what effects they may have on others and the planet. To try to get people to vote for candidates that believe in climate change and aren't in the pockets of the fossil fuel lobby. And to make people understand that it isn't too late. That if we act now we can turn this massive problem around. Unfortunately when we made the film, the U.S. was moving in a very good direction to try to curb this issue. We now have an administration that might as well be a who's who for the fossil fuel industry that is doing everything they can to deny that climate change is man made and even a problem.

Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share?

FS: One of the most inspiring people I have ever met in my life, I had the pleasure of meeting while making this film. His name was Piers Sellars and he was an astronaut and scientist at NASA. He broke down the actual facts about climate change for Leo and myself using the most advanced data available to man. He was also dying of pancreatic cancer and wanted to make it his final life's mission to make people aware that we have to stop pumping so much carbon and methane into the atmosphere before it is too late. Piers was a beautiful soul and passed away soon after the premiere of our film. But he stays with me and helps me fight this issue on a daily basis. What's next? FS: Quite a few exciting projects on the horizon. I am going to direct a feature film called Palmer about an ex-con and his unlikely father-like relationship to a young boy who likes to dress as a girl in a rural American town. Also, I am working on another is a documentary on the ocean and shark activist Rob Stewart, who lost his life recently while making a film on saving sharks. We want to make sure his story is told and his mission lives on.

Anything else you want people to know?

FS: When we were making the film, we were told that we would start seeing unusual storm patterns, and experience floods and winds to the likes we had never seen before. We didn't think it would be a year later! We need to fight. Now more then ever, now with this Trump Administration full of these fossil fuel lobbyists, it is going to be more and more difficult to ensure the lives of our children and grand children will not be endangered due to climate change. Thank goodness many states are taking climate change in their own hands and making huge strides. They are the hope! Stay engaged and make a difference in your everyday life when you can.

0 Comments

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

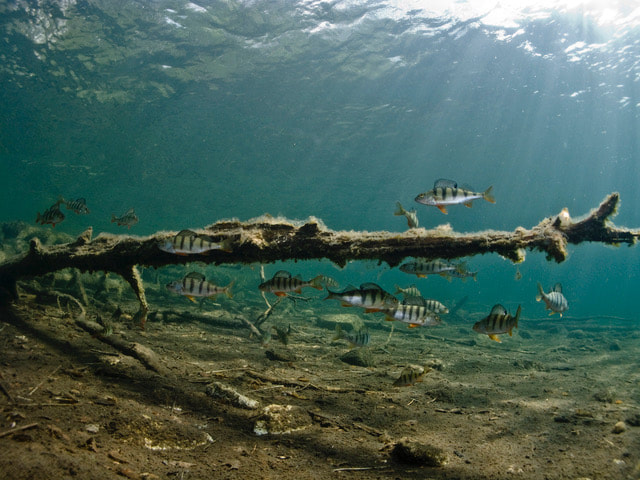

Marko Rohr, Producer and Director: Nature and especially the Finnish lakes have been very important to me all my life. I always knew that the lakes in Finland are something special and that the whole world should know about this unique and wonderful nature that still exists, just as it has been since the end of the Ice Age. As a filmmaker I want to take the audience into this hidden world and tell about the ancient Finnish myths and beliefs that still are an important part of our culture. I am very happy, that in Tale of a Lake I found a way to combine these two elements and can share these experiences with the audience. Very few humans can have a chance to visit these places themselves but the film travels around the world. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. MR: In the nature things happen according to the seasons and here in Finland the seasons are short. We say that in Lapland we have eight seasons and majority of the seasons are in the winter. This means that some animal behavior happens within just a few days. If you can’t film it now, you have to wait for a year to have your next chance. This means we needed a long time to shoot the film, altogether over 600 shooting days within three years. Lots of diving in the lakes, under the ice and filming in the wilderness in ice caves and other wonderful locations.

How do you approach your storytelling?

MR: I have a very long preparation time. My first notes concerning Tale of a Lake date back 20 years, when I was making a series about shipwrecks and was diving with my team in several lakes. After that I was collecting information and making notes of all places I visited and dived and when the time was right I finally had a chance to start filming. I have worked with my scriptwriter in numerous movies, both feature films and documentaries. He works on the storyline and I concentrate on those parts of the script that are based on certain animals or locations. We start filming with wide scope and after the first year of shooting select material, locations, animals and events that support the storyline. Then we concentrate on these elements and try to shoot maximum amount of material to have enough footage for the editor to complete the scenes for the story. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? MR: Some of the scenes that we managed to film were seen for the first time and there were no exact research data when and where they take place. This kind of things were e.g. lake salmon spawning, the rising of underwater mist in the big springs and the formation of ice caves in the rapids. We needed this kind of mystical material for the story, which tells about the ancient beliefs and myths that have been the guiding principles for the ancient Finns and have determined their relationship to the nature. At times it was the nature directing us filmmakers!

What next?

MR: I have started the production of the final part for the trilogy about the Finnish nature and myths: Tale of a Sleeping Giant. This film is a mythical tale that begins billions of years ago, when the first mountains on Earth were created. Slowly the mountains have moved to far up north with the tectonic plates. Over millions of years the mountaintops have eroded and the ancient roots have appeared on the surface of the Earth. Those roots are the Lapland fells; the oldest mountains in the world. In the old Sámi mythology, the fells are sleeping giants. In winter they are in deep slumber and move across the starry skies, but in summer they have colorful dreams. The movie tells about nature in the winter, spring, summer and autumn in the fells. It continues the narrative style of the film Tale of a Lake and will be shot in Lapland 2017-2019. The film will be released in 2020.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Planet Earth II: It's a relatively new concept to think of the urban environment as a habitat that can be suitable for wildlife. When I first took on the project I was hopeful that there would be lots of new and surprising stories from this environment. I was also aware that this episode would help to give a snapshot of the state of our planet. Wildernesses are in decline, one study has recently showed that global wilderness areas have decreased by 10% in just the last 20 years. In contrast, the urban environment is expanding and evolving very fast. So it is a fascinating growing area of research to look at how animals are overcoming the challenges of living in our cities. And it is an interesting question to ask as to whether we will choose to maintain a connection to nature here. That's an important question because more than half of us now live in the urban environment, and we of course are the architects of this world. So both the connection we maintain to nature and the fate of wildlife in our cities is in large down to us.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

Animals move through the urban environment unaware of who owns which bit of it. To film peregrine falcons in New York City we needed to use a helicopter to gain access to many rooftops of skyscrapers across the city. It took one person 9 months, full time, just to secure the permissions for this filming! What impact do you hope this film will have? For city dwellers many scientific studies have shown that simply looking at a view of nature calms us down and lowers our stress levels. Now that more than half of us live in the urban environment I believe that keeping a connection to nature here is more important than ever. I hope that this film will inspire people to do what they can to green our cities, welcome in wildlife, really make space for it and enjoy having nature on our doorstep. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? When I first heard about spotted hyenas freely running through the streets of Harar, Ethiopia, I couldn’t quite believe it. The story goes that over 400 years ago when the city walls were being built ‘hyena gates’ were incorporated… not big enough to allow in an opposing army, but just the right size to let a hyena through. Now two hyena clans enter the city through these gates every single night in search of bones left out by the town butchers. I know, first hand, just how ferocious these animals can be, and whilst walking down a narrow cobbled street, on my first night in the old town, I held my breath as eight hyenas walked past me brushing my leg. A few nights later I was filming a clan war - the two dominant hyena clans were fighting over access to the city. Over a hundred hyenas were battling around my feet and somehow my fear had disappeared. The peaceful pact between people and hyenas in this city was so evident that I didn’t feel at danger of them turning on me. I am told that inside the city walls the hyenas never attack humans or livestock, but why are they welcomed in? Spotted hyenas are possibly the most vilified animal on our planet, often associated with witchcraft, but here the local inhabitants believe that each time they cackle they are gobbling up a bad spirit in the street. It’s a truly remarkable example of how man and beast can live alongside one another harmoniously.

Did the film team use any unusual techniques or unique imaging technology?

The most innovative filming technique used on Cities was ‘Flow motion: hyperlapse’. The ambition behind these sequences (City intro, Hong Kong city lights and the Vertical Forest in Milan) were to go on a continuous, seemingly impossible and magical journey through the urban environment. Where we could we used transitions rather than cuts to give the feeling of flowing on a journey through the city. The technique condenses space and time by moving time-lapse cameras through the environment. It is a highly complex technical feat involving simultaneously filming one scene with many cameras and expertise in blending the different shots in post. It is a bold technique because you commit to the transitions between the shots in the field, you can’t then change the sequence order in the edit!

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Chasing Coral filmmakers: This story really came to us through Richard Vevers. He emailed our team after seeing Chasing Ice and told us there are dramatic changes happening in the ocean and that it is a very visual story that the world needs to see. So we started following him, meeting and interviewing scientists, and discovered for ourselves how quickly reef ecosystems are changing. We knew this was a story that needed to be told. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. When you are working on documenting something that has never been done before, there are inherent challenges. It was a grueling production involving new technology issues, working in an ocean environment with currents, storms, underwater filming, communication challenges, time-limitations with oxygen tanks, and so much more. We were lucky to have a skillful and talented team to help keep us afloat (literally)!

How do you approach storytelling?

We knew that film has the potential to create empathy and we felt that a human-centric story was critical. We also recognized that in order to tell a story about an ecosystem collapse, we needed a way to show that story visually. If we could capture a time-lapse of a reef's dramatic changes, we would be able to show that transformation as a visual documentation of our changing planet. We also learned so much from the making of Chasing Ice and our mentors that we began working on possible narratives early on in order to make sure that the footage we were capturing was resonating and forming a compelling story. What impact do you hope this film will have? We believe in the power of film to activate individuals, mobilize communities and build bridges. We are working on making sure that this film gets out into the world in a powerful way. Since we premiered on Netflix, our goal is to support screenings globally through resources that empower audiences to mobilize locally. We are also working with diverse partners to spark local movements around sustainability, and we seek to engage leaders to help us acceleration what Richard calls the "great transformation".

Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share?

The most surprising part of this film has been gaining a real understanding of what is happening in our oceans. For example, it is hard to fathom that 93% of the heat from climate change is being absorbed by the ocean. That is a massive amount of heat. When our team watched these changes happening right before our eyes, it really was a shock and it changed the way our team looked at this problem. Anything else you would like people to know? This was a story that took three and a half years to make, hundreds of hours underwater, and is a culmination of the hard work of people from around the world. We hope viewers will share this story and film as we know that the first step towards action is awareness.

What next?

While we don't have anything currently in production, we are always looking for the best stories to tell. Questions for specific categories: Impact What do you see as the impact of the individual, group or movement featured in the film? We owe a lot to Richard, Zack and the scientists in this film. They are really the ones who have devoted their lives to giving a voice to the corals. Through his photography, Richard has given this issue a face and without him, we would still be ignorant to this massive problem. Zack has given a heart to the issue and through his love and obsession for corals, we feel his pain for their devastation and demise. Obviously, the mind and brains of the operation come from the scientists but they also are so much more than facts and numbers. These people have dedicated years of their lives to studying something that is rapidly disappearing, and yet they get up and go to work every single day. Their strength is comparable to the resilience that reefs can have if we only give them a chance.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Lens of Time Filmmakers: As science and nature filmmakers, we’re always searching for ‘veiled wonder’ - basically the marvels that are hidden in plain sight in the mundane everyday world. In discussing ideas for a new short-subject science series, we realized that scientists who work in ‘time dilation’ – using high speed or time lapse cameras – have opened some amazing trap doors into those portions of the natural world that are typically unavailable to us. These scientists are searching for the secrets of life’s inner workings that are obscured in the folds of time. And every day they’re inventing new techniques (and technologies) that can take us to places we’ve never been and reveal some of life’s deepest and most profound principles. We believed these stories would inspire viewers to look at the world with a fresh eye, and would remind them that there is so much wonder hidden right in front of them, and all that's required is an awareness to see what was previously unseen. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. It is important to us that the story behind every episode in this series be told directly by the scientists themselves. And equally important was that the scientists illuminate their process. Where does the spark of their idea come from? How do they design the experiments? We want viewers to develop a sense of how we know what we know. The big challenge with this kind of storytelling is surprisingly simple: Some people are just more articulate than others. Just because a scientist is brilliant, innovative and accomplished doesn’t mean they’ll be good at explaining what they’re doing. We attempt to choose our scientists carefully, making sure they can communicate their passion for the subject and balance that with a clean explanation of process. But sometimes it simply comes down to time: We needed to add days, schedule remote recording of additional commentary, or simplify the story to make sure that the core question and the arc of the science remain clear and elegant.

How do you approach storytelling?

For this series, we focus our storytelling approach on creating a sense of “time travel” in the narrative. The central idea is that the viewer literally needs to slow themselves down (time lapse video) or speed themselves up (high-speed video) to enter the timeframe of a non-human species, whether that’s a slime mold or a jumping spider. In each instance, the research scientists are the guides, recalibrating the viewer and instructing them on what they’re seeing in this new, foreign time domain. Again, it is important to make sure that the scientists feel more like guides than containers of factual knowledge. That allows the story to function as trip to a destination where a new behavior is revealed, and not simply a lecture by a “voice of authority” who elucidates facts.

What impact do you hope this film will have?

Our goals with this series are simple: 1) Demonstrate how simple observation and logical investigation can help to unravel the seemingly impossible complexity of the natural world. And 2), demystify the scientific process and make it clear that anyone who keeps their eyes (and brain) open can visit species and territories of the Earth that have been invisible to them up to now. If viewers watch an episode of Lens of Time and suddenly find their back yards more dramatic and interesting, then we’ve succeeded. What next? We’re gearing up for a new short series on the greatest ideas in ecological science, the women and men who originated them, and the new generation of ecologists who are following in their footsteps, generating an entirely new set of ideas about the way the world works.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Sonic Sea filmmakers: Sonic Sea was inspired by the devastating impact that ocean noise pollution is having on whales, dolphins, fish and other marine life. Intense noise from naval sonar, airguns used in oil and gas exploration, and heavy ships are destroying the ocean’s delicate acoustic habitat, threatening the ability of whales and other sea creatures to prosper and even to survive. We made Sonic Sea to raise awareness about this problem and to propel solutions before it’s too late.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

The biggest artistic challenge we faced is that Sonic Sea is a film about sound...sound that most humans never hear. That meant coming up with a visual vocabulary to depict the complex acoustic world of the ocean, and creating a score and sound design that completely immerses the audience in this rich and unfamiliar soundscape. How do you approach storytelling? Sonic Sea tells a complex scientific story, but we knew it had to be grounded in human narrative and emotion. We structured the film around the story of Ken Balcomb, a veteran Navy acoustics expert and whale scientist who worked heroically to prove to the Navy that it was killing whales with sonar.

What impact do you hope this film will have?

We are deeply gratified to see that Sonic Sea already is making a difference. The film helped spur the release of NOAA’s long-delayed ocean noise strategy; helped convince the Canadian government to commit to reduce shipping noise in key habitats; was instrumental in General Electric collaborating on an industry consortium to reduce shipping noise; led to a partnership with Maersk, the world’s second largest shipping company, to launch a pilot project on vessel retrofits and noise reduction; and was widely used by grassroots advocates in last year’s successful fight—now renewed during the Trump administration—against seismic blasting off the mid-Atlantic and southeast coasts. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? One of the most meaningful experiences in making Sonic Sea was to see the emotion that drives some of the world’s leading marine scientists and ocean explorers. Their personal stories about interacting with whales were so moving that we built a whole sequence of the film around them.

Anything else you would like people to know?

The ocean is an acoustic environment. Sound travels fast and far in salt water. Much farther than light. That’s why so many life forms in the ocean use sound to communicate, navigate, hunt, and raise their young. We need to respect that. Which means making a lot less noise. We have the technology to be much quieter. It’s just about making the choice. Let’s allow all of the singing voices of the planet to be heard. What next? We’re hoping to make a film that looks at climate change in a new way: through the eyes of America’s soldiers.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Director and Producer James Reed: I first got interested in this story while studying footage of a chimp called Pincer years previously. There was something very strange about him I thought and after a while I realised what it was. He had human eyes – white sclera around the outside of the eye which allowed you to follow gaze, see where he was looking. I did a bit of research and discovered that according to the scientific record, officially chimps don’t have this. It is a uniquely human trait, which evolved with our own advanced cooperation. Then I discovered that Pincer was a member of the largest and most violent chimpanzee community ever known and that they had been studied and filmed by scientists for the last 25 years. That inspired me to look into what happened across that 25 year period and that’s when I came across a story that is as epic and dramatic as any feature film.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

JR: Condensing an extraordinary 25 year true story into 90 minute film was one of the biggest challenges. Simply going through decades worth of video recordings taken by the Ngogo scientists was a huge undertaking. They came out of a dusty box at Yale University about a year before the edit and I spent months trawling through hundreds of hours of footage, searching for story threads with specific chimpanzee characters. Often the challenge is finding enough story to fill a film, but with the Ngogo chimps, and the scientists who study them, deciding what to leave out was the biggest challenge.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Maramedia: We’d wanted to make a series about the Highlands for years, but it took our small production company about four years to develop the local expertise and field people to do it well enough to match our ambitions. We wanted to make the series authentic. We used no stunt animals, spent years working out the best way to film each story and put an exceptional level of work into the music and sound – more than I’ve ever spent on any project before. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. Maramedia: Our team was embedded in the wild habitats we filmed in for more than two years which meant we were well equipped to deal with the constant change. Scotland’s climate is one of the most changeable in the world. It can be warm in Winter, freezing cold and snowing in late Spring and pouring with rain at any time! We were keen to capture a short sequence of dippers at the nest on a gently meandering Highland river, but during our schedule in May, we had some of the heaviest and most intense rain this part of the Highlands had seen in years. But we just had to stick it out as the ways that the wild mammals and birds deal with these extremes gave us the best stories in the film. We deployed our camera team on the dipper nest in rotations as we never knew when the chicks would fledge and as we waited, it rained more and more and more and the river just kept on rising. In the end, what was supposed to be a 3-day shoot turned into a 2-week epic with 5 chicks finally emerging to face a river which had turned into a real torrent, more like Niagara than a gentle Highland stream!

How do you approach storytelling?

Maramedia: I’ve been playing around with story for years and have always loved the idea that you can break a seasonal wildlife tale into 5 acts rather like a Shakespeare play and concentrate on the different bits to bring out your innate comedy, tragedy, heroes, villains and countless other themes. We didn’t have to work too hard in the Spring show to achieve a satisfying result. The other thing that helped pull everything together was the way we worked with music. Our composers – Donald Shaw and Simon Ashdown worked with us from very early in the process composing themes and beds after just looking at rushes. They then worked directly on textures for the film with the offline editors rather generously amending and changing each other’s sections – sometimes a dark theme would turn into something light and airy and at other times they found ways of injecting light into the musical darkness. It was a very satisfying process and then close to the end all the music was re-recorded with as many live players as possible. We ended up with something which was full of melody as well as complimenting the pictures beautifully. Anything else you would like people to know? Maramedia: Well I’d like people to know that we did this project on limited resources, but like our previous productions it got great ratings and has had some decent awards nominations. People like the two composers and Ewan McGregor got behind it for reasons other than commercial ones. But the common denominator is the authenticity which springs from an intimate relationship with the people on the ground and the wild animals themselves. That means we can compete on an international stage despite our entire budget being significantly less than the shooting budget for a single episode of something like Planet Earth 2 or the Hunt!

What next?

Maramedia: Such passion and dedication from so many people went into making this film. But wildlife filmmaking is just like childbirth – once you’ve produced your programme you forget about all the pain and the hard work, love the outcome and want to do it all over again! We are currently filming an exciting new documentary on the amazing wildlife of the Shetland Islands as well as Wild Way of the Vikings which mixes stunning wildlife spectacle with the gripping story of the Vikings relationship with nature in an exciting new format. We are also thrilled to be making an inspiring new series for CBeebies BBC in UK – ‘Gudrun - The Viking princess’ which encourages children to explore and be inspired by the natural world through play. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

Contact UsJackson Wild

240 S. Glenwood, Suite 102 PO Box 3940 Jackson, WY 83001 307-200-3286 info@jacksonwild.org |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed