|

We reached out to Marc Levin and Mark Benjamin to ask them five questions about the experience of making their film.

What inspired the story?

The idea of an over exploited 'wild fish-less’ ocean was incomprehensible. That the ocean could die in our children’s lifetime is too much to fathom. That is why the filmmakers made Ocean Warriors. We wanted to do a crime series with action on the high seas - we wanted it to be an adventure, a thrilling ride that involved and stimulated the audience instead of preaching to them. We wanted people to see how daring and exciting it can be to try and save the ocean. We wanted them to see young activists with boots on the deck, not lecturing about it, but doing it. And we wanted to show that you can win! Describe some of the challenges faced while making the series. Too many fishermen are chasing too few fish. We are taking fish out of the ocean faster than fisheries can replace them. More than three quarters of the world's fisheries are in a state of collapse. We wanted to tell an international crime story with real life sleuths and activists who are fighting to save our oceans. The production challenges were daunting, but nothing compared to the challenges we'll face if we don't stop those plundering and murdering our oceans. Centuries of belief that the ocean’s resources were infinite and our callous disregard even when faced with collapse have brought us to the brink of an environmental catastrophe. We continue to overfish and destroy the very system that supports life. Ocean Warriors, this six-part documentary series, took viewers to the frontlines of the battle to save our planet’s first ecosystem, the origin of all life on Earth.

How do you approach storytelling?

We worked with established groups like Sea Shepherd and Greenpeace as well as individuals like Jim Wickens, Michael Markovina and JD Kotze. The decision was made to go for an editorial weave with one ongoing series story, the chasing of the Interpol Purple notice listed outlaw vessel the Thunder. The epic chase for the world's most wanted poacher ending in a surprise no one saw coming became the spine of the series. Finding the balance between the ocean science and the verite scenes was our challenge. If you capture the true characters on the frontlines and all the dramas they face, so that the audience is fully engaged, then you can offer them the follow up materials that enlist, educate and advocate. The idea is to get their hearts beating then open their minds, this was our goal. Unlike farming, ranching or mining, the tragedy of the ocean, the commons … the fishermen do not sow it, hoe it, or grow it, seed it, feed it or weed it. There’s only massive extraction of the fish, and to many of the fisherman, fish are money swimming through the water. What impact do you hope this series will have on audiences? Ocean Warriors weaves multiple stories of courage, conflict and change, from the Antarctic’s remote Southern Ocean, to the coral reefs of Tanzania and the vast tuna fisheries of the Western Pacific. We set sail as a global coalition of activists, campaigners, scientists and investigative journalists prepared to stare down poachers, tear up illegal poaching networks and bring the outlaws to justice. We hope our series causes a new awareness to the dire state of the ocean.

Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share?

The big idea for us was to serve ocean conservation as entertainment and not medicine. The direct-action activists in Ocean Warriors deliver adrenaline and high octane adventure in their fight to save the ocean. They put their lives on the line and filming this struggle was meaningful. Anything else you want people to know? "Our oceans are earth’s lifeblood, providing us with the air, water and food we need to survive. Sadly, they are in crisis due to climate change, pollution and illegal over-fishing. Ocean Warriors profiles the stories of the dedicated women and men who are taking up the charge to protect our oceans for future generations and is a call to action to join the cause,” said Robert Redford, Executive Producer of Ocean Warriors. “The challenge of restoring ocean health has never been more urgent. Our oceans are complex living systems that help feed millions, mitigate climate change and even yield lifesaving medicines. I am proud to collaborate with Robert Redford, Animal Planet and Brick City TV to bring awareness to this critical issue and inspire people to change the way in which we care for our oceans. While our oceans may appear infinite, ocean life is not. We must act now to save it.” Paul G. Allen – Executive Producer of Ocean Warriors.

2 Comments

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story?

Producer, Writer and Director Andrea Heydlauff: I had been working in big cat conservation for many years and was too acutely aware of the giant challenges big cats are facing around the globe – from relentless poaching for their skins and bones, killing from conflict with livestock and humans, and habitat loss and fragmentation. But I knew there were locally relevant, scalable solutions –stories that show that hope isn’t lost and there’s reason to keep forging ahead. I had known the co-founders of Lion Guardians, Leela Hazzah and Stephanie Dolrenry for years, and admired their model of how it saved lions and changed peoples’ lives. They told me about a young Maasai boy who had never seen a lion in the wild but whose father (who was a Guardian) took him into the bush to see his first lion; and in preparation this little boy put on his church clothes. I was moved to tears and thought what a gorgeous and hopeful story– of people who traditionally killed lions who were now putting on their best clothes to greet them. We actually had Lion Guardians come to Akagera National Park in Rwanda, a park African Parks has been managing since 2010 when we brought back lions in 2015 after 10-years of being absent. How do you approach storytelling? AH: I love stories that move you, that make you feel something - and ideally those are feelings of hope, inspiration, surprise, and even love. I look for real stories about conservation from unlikely places, and like to focus on the positive. I think we need to balance the doom and gloom of what’s happening with wildlife and also tell the stories of change – of survival, resilience and the extraordinary efforts of people who are coming together to help save species and wild places around the globe. As the Chief Marketing and Communications Officer for African Parks, a conservation NGO that manages protected areas across Africa, I focus on these stories from the parks we manage and find people are often more inspired to get involved based on hope, rather than fear. What impact do you hope this film will have? AH: I hope this film helps Lion Guardians with telling their story, of their impact, and how they are changing people’s lives and saving lions – whether that’s through getting additional donor support to shining a light on the Guardians themselves, to helping inspire local communities that there are solutions to living with lions and other big cats. The film will be translated into Ma and Swahili and I hope the Lion Guardians can use it as one of their tools to engage their local audiences, and help protect more lions.

Anything else you would like people to know?

Before they started in 2007, people were killing lions in response to the threat of lions killing their livestock, while at the same time carrying out a rite of passage. Lion Guardians changed that paradigm. They’ve hired and trained more than 80 Maasai and other pastoralists to track lions, prevent conflict by working with communities to reinforce bomas (lion-proof corrals), retrieve lost livestock and stop lion hunting parties. And they’ve reduced lion killing by more than 90%. That’s extraordinary - it’s a story of how local people who once threatened the lion’s survival have now become their salvation. What’s next? I’m working with an extraordinary team out of Cape Town, South Africa called Green Renaissance and have a few short films for African Parks underway, one of which is about our efforts to return rhinos to Rwanda which we just completed in May 2017. Eighteen Eastern black rhinos were translocated from South Africa to Akagera National Park in Rwanda (which African Parks has been managing since 2010) returning the species to Rwanda after a ten-year absence. And I’m wrapping up another short film about one of the largest elephant translocations ever completed. We just finished moving 520 elephants to a new home in Malawi from two parks to a third – all of which African Parks manages, to help repopulate the park after years of poaching. These stories are about restoration, and showing the world what’s possible.

By Abbey Greene

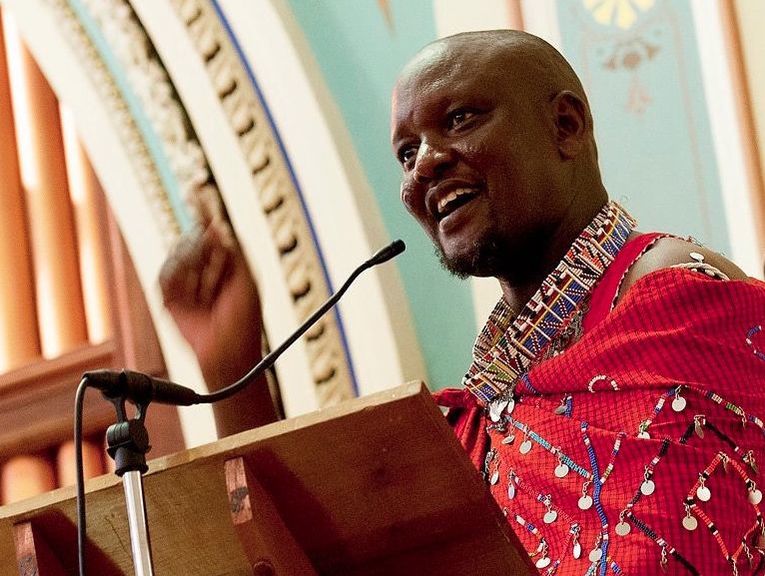

Daniel Ole Sambu is an elder in the Maasai community, a natural leader and dedicated conservationist. He has over 10 years of experience working with communities and partners to protect the Amboseli-Tsavo ecosystem and its predators. During his time with the Predator Protection Program he has helped significantly reduce retaliatory killing of predators, namely lion.

Q&A:

Dereck Joubert's new film "Tribe Vs Pride" features your tribe's relationship with lions. Why is this story important for conservation efforts?

Daniel Ole Sambu: I am very excited to see the film premiered at the Jackson Hole Wildlife Film Festival. To me, telling this story this will really help our conservation education team and the Maasai Olympics, two of our programs to help the Maasai cohabitate with lions in Kenya. It’s a brilliant presentation of the Maasai versus lions, where the Maasai’s have to make a far reaching decision to bear the losses of living with the lions, and to protect the very lions that kill their livestock. What is your own personal relationship to lions? Sambu: Just like any Maasai young boy, since childhood I also have the same spirit of killing a lion to prove my warrior-worth. Because killing a lion is prestigious culturally, I participated in five lion hunt attempts but never succeeded, although my friends did. It's the duty of every warrior to protect their family’s livestock from any outside intrusion, including lions. After a while, I became employed to protect lions from, among other things, cultural killing! So it’s now me between lions, warriors, and livestock. I am supposed to use my social character to bring peace and tolerance between livestock owners and the lions. I have come to realize that predators, lions in particular, form an integral part of any conservation initiative. Eventually, working with Big Life’s predator protection program, the lion which I wanted to kill has become my most favourite animal.

Tell us about Big Life's predator compensation program, which you manage in Kenya. Why is it successful?

Sambu: Started in early 2003, the predator protection program is a partnership between Big Life Foundation and the Maasai to address the imminent threat to lion extinction. In collaboration with the local Maasai community, Big Life works to try and better balance the costs and benefits of living with wildlife, replacing conflict and retaliation with tolerance. Since inception, we have witnessed lion killing virtually stopped on the three group ranches where we have the predator compensation fund. The fund was set up when we realized that the Maasai community is affected so much by the economic losses of their only source of livelihood, which is livestock. Essentially, if a lion kills livestock, the owner of the livestock is entitled to partial compensation. The compensation fund involves a 27-clause agreement explaining the roles and responsibilities of each partner, and with stiffer penalties for negligence and lion killing, have made it one of the most successful compensation programs in the region. We think it’s the biggest hope for lion survival in the pastoralist dominated ecosystem.

How can people in the U.S. support the lion conservation work you do in Kenya?

Sambu: By making a donation in support of Big Life’s predator protection program, you will be guaranteeing lion survival in this ecosystem, and support expansion of the program to areas that have have yet to receive any benefits from conservation. You can also visit as a tourist these areas outside the parks, and the dollars you pay in those lodges will support the conservation of lions. Finally, supporting our scholarship program enables children from less fortunate families attain the most needed education, thereby creating a very understanding community. Through this program, employment opportunities are created, directly improving the living standards of the local Maasai and helping to conserve lions.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

Still image courtesy of To Skin a Cat Still image courtesy of To Skin a Cat

What inspired this story? I visited a Shembe gathering years ago. I was appalled by the number of leopard skins being worn by dancers. At the same time, I was both intrigued and moved by the beautiful sense of meaning within the ritual. I think the film was inspired by tension between those two contrasting experiences of the same event.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film.

Our biggest challenge was coming up with a solution that worked for both the conservation bodies and the Shembe Church. Building an open line of communication between ourselves and the Church was a difficult process.

How do you approach storytelling?

We realize people aren’t going to watch something just because it's an important or critical issue. They need to be entertained. And to do that we needed to have character development and narrative arcs, but within the restraints of a real life story, the pace and direction of which we couldn’t dictate. We learnt that sometimes you need to push in a certain direction as a story teller and other times you simply have to wait for the story to evolve of its own accord.

What impact do you hope this film will have?

Our goal has been to protect leopards, primarily from people not knowing or understanding the threats they face, and to use entertainment as a way of doing that.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired the story?

Producer Sam Suter: As a team team we were moved by these individuals. They are geniune, passionate, humble and knowledgeable. It was a privilege to spend time with them. Some of those featured in the film are part of the anti-poaching init at Ol Pejeta, some manage human-wildlife conflict in the area, and others are the caregivers and protectors of the last remaining white rhinos on earth. These animals are gaurded 24/7 at the conversation. There are only three northern white rhinos left in the world – Sudan (the last male northern white rhino at 43 years old), Najin (Sudan’s daughter at 27 years old) and Fatu (Najin’s daughter at 16 years old). They all were raised in a zoo in the Czech Republic and were brought to Ol Pejeta in 2009 in the hopes that they would breed in a more natural environment. Sadly all attempts at breeding have been unsuccessful thus far and Ol Pejeta, alongside other individuals and organisations are working hard to attempt to use IVF (In Vitro Fertilization) technology to save this subspecies from extinction. Our hope is that this will be successful and we can one day have a steady population of these magnificent rhino again. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. SS: One of the biggest challenges was dealing with very sensitive animals such as rhino’s coupled with the fact that they were the last three northern white rhino’s on the planet. This meant at all times we had to be within a safe distance from the rhino as to not disturb there daily routine as any form of stress can have dire consequences. It also meant that the amount of time we had with the rhino’s was very limited so we had to maximize the few hours we had on a daily basis, to tell the whole story, which is never easy. You are also dealing with an animal that can be very unpredictable on its day so one would always have to listen to the rhino caretakers and follow their lead. How do you approach story telling? SS: The fundamental part of story telling is to give the audience a good idea of what message you are conveying in an allotted amount of time. The viewer needs to walk away after watching your film, knowing that their perception has been altered as a result of what they have just watched. To tell that story you need to identify key characters and key themes and then build an emotive story line around those factors that will captivate the audience. As with all film making planning is key as a well planned production will go a long way to accomplishing a strong narrative. So know who your key characters are and know what your message is that you are trying to convey. Working with wild life and endangered species, we are very sensitive when filming and always aim to document people and nature in a genuine way, connecting with our subjects, ensuring depth to our video product. What impact do you hope this film will have? SS: United for Wildlife, through this film, aims to give Rangers a voice. They are the ones fighting the war on the ground and working tirelessly in the field to protect our wildlife. And it’s about time we celebrate these men and women that are doing this work all over Africa, and the world. These are people with incredible insight and knowledge. Amongst them you will find skills and expertise that have been fine tuned to deal with everyday challenges like we could never imagine dealing with. They are doing good work and its key to help them expand upon what they are doing. Often we focus on the wrong individuals when it comes to controversial topics like conservation – and it is about time the world tuned into what people in the thick of it have to say about wildlife in Africa. This film focuses on the rangers working at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy – but they represent so many other rangers – men and women. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? SS: It was meaningful, sad and an honor to meet Sudan – the last make Northern white rhino. We have filmed the Southern white rhino many times in Southern Africa and we did not expect that these two subspecies of rhino would be so physically different. We were taken aback by this amazing prehistoric beast and the crew just fell silent from spending time with him and coming to the realization that these three white rhinos are the last of this subspecies, It was hard hitting. The Northern white rhino has a larger head, shorter legs, hairer ears and other features that make it different to the Southern white rhino. Sudan is incredible as such a large rhino, with incredible presence and amazing relationship with carers. Meeting all three of the last Northern white rhino – Sudan, Ninjin and Fatu was amazing.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

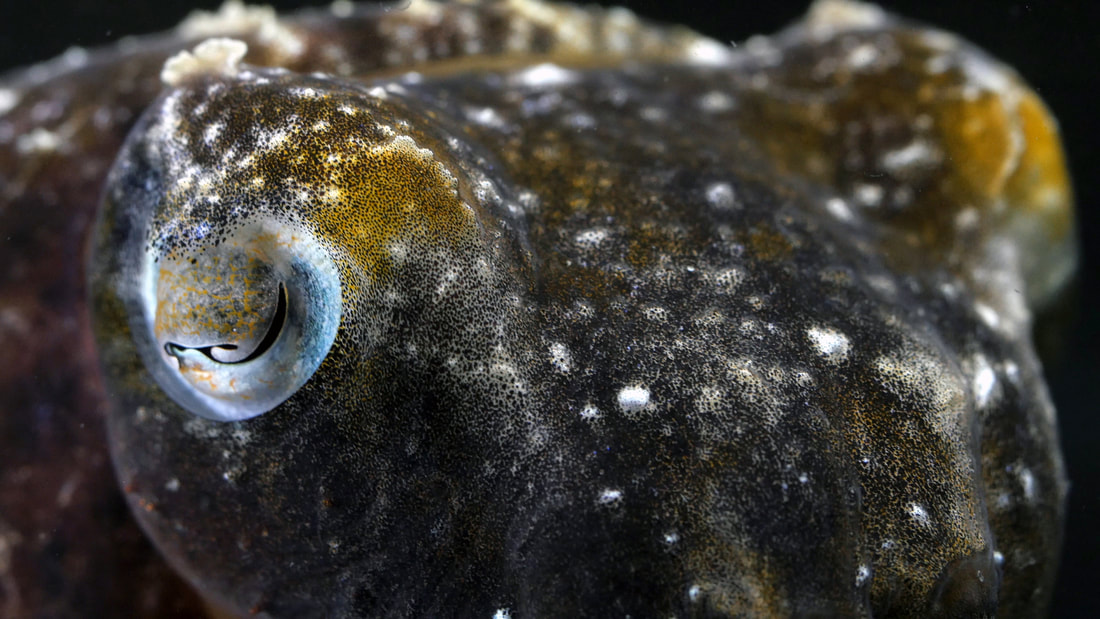

What inspired this story? Elliott Kennerson, Producer of Deep Look's Caddisfly episode: A scientist from UC Berkeley approached us with the idea when we were doing a screening at the university. Little did we know that these caddisflies were such prominent locals! They are everywhere in Northern California’s rivers and streams just after the snowmelt. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. EK: We brought specimens into our studio and tried to replicate natural conditions to induce the behavior. The biggest challenge was keeping those conditions up…especially the clean, cold, turbulent water. Without these conditions the caddisflies weren’t likely to build their little houses at all. It was a nail-biter for a good 24 hours as we watched them doing very little! How do you approach storytelling? EK: Since our show is poetic in nature, I try, frankly, to imagine what it would be like to be the animals that we film and see the world through their eyes. What would it be like to live at the bottom of a turbulent stream? How would I survive? Anything else you would like people to know? EK: We edit in Premiere and finish in After Effects. I was very proud to be the one to do the full AE phase on this episode myself. I may have earned my After Effects badge here! What next? EK: The series continues! Next I’m tacking bats, black widow spiders, and cactus spines.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story? Martin Dohrn, Producer and Director: As a film maker who has spent a significant amount of my filmmaking time in the dark, the worldwide prevalence of utterly entrancing bioluminescence was always apparent. I realised that bioluminescence was a significant part of nature rather than a minor scientific curiosity, and that there were enough spectacular examples to tell the story of living things that glow, in a way that had never been achieved before. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. MD: Bioluminescence is a huge subject, touching on almost every realm where life can be found, and so finding a clear thread through hundreds of papers, eyewitness accounts and subjects that were actually possible to film, took years of investigation. For a subject so little known, it was hard to raise funding, but after many years of persuasion and arm twisting, Terra Mater Factual Studios came on board and supported us. The images themselves also needed cameras and previously untried filming techniques, to record pictures in light levels where the human eye can barely see. How do you approach storytelling? MD: David Attenborough's presence in the film allowed us a greater licence to stray from the tabloid and into a scientific world while keeping the feel of the show popular and accessible. This gave us freedom to use evolution, function and habitat to connect seemingly different kinds of bioluminescence. David Attenborough's presence on screen also helped to give scale to what might have been otherwise quite abstract images. What impact do you hope this film will have? MD: I hope that people will be able to understand that the daytime world we inhabit is just one realm of life, and that a few people will be motivated to discover a whole new planet Earth. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? MD: To be on the ocean at night under a clear starry sky, watching as the wake of the boat creates spectacular light trails, that are then framed by a pod of ghostly, cavorting dolphins, lit only by the light they create as they cut through the water, has to be one of the most magical experiences of my life. What next? MD: We are making a series about the seven living big cats, their prehistory, their history, their present and future, for CuriosityStream. We are also making a film about a giant ant supercolony with David Attenborough for BBC and Terra Mater. Why did you pick David Attenborough to be the on camera host telling this story? MD: David Attenborough of one of the few people who have ever presented a film about bioluminescence in the past, and his encyclopedic knowledge of the subject made it easy for him to convey genuine understanding of the story. His presence in the film allowed us a greater license to stray from the tabloid into a scientific world while keeping the feel of the show popular and accessible. David Attenborough's presence on screen also helped to give scale to what might have been otherwise quite abstract images.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story? Darcy Riggins-Schmidt, Wildlife Media: Ecologist Chris Morgan is on a life-long quest to bring the wonder of bears to the world. And it all started in a garbage dump! While working on a summer camp as an 18 year old in New Hampshire, he joined a local bear biologist capturing black bears one night and it altered his life path. Positively overwhelmed by the wild adventures and the heart-melting experiences he experienced during his work as an emerging conservationist to several international locations over the following years, Chris was determined to share them with the world. Chris believed that if he could transport audiences to the world he was experiencing he could win over people of all backgrounds to support bear conservation, and to understand the basic truth he had discovered: What’s good for bears is good for people and the planet. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. DS: We went to extremes of the bear world - from the ice-bound arctic to the rainforests of Borneo and the high Andes deserts of Peru (following cliff-climbing bears in 106 degree heat). Each place brought physical challenges, not to mention difficulties with camera equipment, and Chris’s motorcycle exploits! And finding a helicopter to spend our last $3000 on in Borneo in the days before drones was comical, but paid off! But what was a new challenge for this film was breaking new ground when we started out 10 years ago with the idea to fund it from donations. But that challenge became a blessing in so many ways - the journey of making the film surrounded by heartfelt support from over 200 donors became something that will stay with us all. How do you approach storytelling? DS: With BEARTREK we wanted a grand, but authentic feeling. A film that felt somewhere between a feature film and a documentary. Something as big and majestic as the bears themselves. But still something very personal to Chris and the other biologists involved. Allowing Chris’s backstory as an ecologist brings a level of authenticy, and we filmed over a number of years, we were able to return to the featured bear biologists to capture a moving update that becomes the final act of the film. Something we hadn’t actually planned for. What impact do you hope this film will have? DS: BEARTREK was born with impact in mind. Chris’s experiences around the world working with bear biologists on the frontline of conservation during his 20s and 30s was an emotional, and life-altering experience. He knew these people needed two things - exposure...and funding. He conceived of BEARTREK as a way of accomplishing both. And by joining forces with Joe Pontecorvo, John Taylor, and Annie Mize turned a simple film into a quest to support on the ground efforts. We've provided funding to three biologists on three continents, turning to our amazing donors for help when needed. We created a fundraising video from Borneo BEARTREK footage, which helped Siew Te Wong raise significant funding for his sun bear conservation center in Borneo. Robyn Appleton established a brand new national park in the bear country of Peru, with help from our footage to tell her amazing story. And we’ve raised over $100,000 for polar bear research in Hudson Bay for Dr. Nick Lunn's climate change work. BEARTREK has inspired half a dozen TV series, including ‘Bears of the Last Frontier’ for PBS Nature, and Chris’s ongoing role as host of that series. Bears of the Last Frontier became part of a larger effort to protect 11 million acres in the Western Arctic, reaching over 3 million people with conservation messaging. We’re very proud of these initial accomplishments before the film has even been released, and we plan to continue this impact as BEARTREK is seen all over the world. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? DS: Wow! So many! Where to start!? Anything else you would like people to know? DS: BEARTREK became an important part of life for our small team. To the extent that the team has become more like a family. The film was made over a period of nine years, and it triggered so many good things that the story got better as we went along. We’re glad to jumped right in, but we had no idea what would become possible. The friends we’ve made, and the good things BEARTREK has been able to support. We would encourage anyone to dive in and start - even if you don’t have a fully fleshed out plan! You never know where it might lead you. What next? DS: Our mission continues to inspire new generations of conservationists and film makers. To become part of a movement that makes conservation a social norm. No small task. People are surprised to hear that if we were to protect the 8 bear species of the world, we’d protect around one third of the earth’s land surface! A powerful statement as a conservation tool to harness. Using what we have learned through BEARTREK, and through our new, related efforts to create short form wildlife content for social media audiences, the potential to reach large audiences and push the needle is real. BEARTREK has always been more than a film, and that story will continue, we’re happy to say.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

What inspired this story? Director Jérôme Bouvier: What inspired this story is the will to make a sensitive film, going beyond a classic expedition film. The discovering of the area by two sensibilities extremely contrasted allows me to speak about Antarctica and tackle the complexity of the phenonema at stake. Slightest change have deep consequences on the species which live there. What impact do you hope this film will have? JB: I hope my film will cause surprise, wonder and empathy so that spectators will have a sustainable interest to this continent, how it works and its protection. So that Antarctica will stay a land of peace and science … And a long time after 2042, year during which the Antarctic Treaty will be discussed. I want my spectators taking conscience that everything is linked on our planet. One action here can have aftereffect other there, far away from here. And also, the complexity of the working of our planet is fascinating and deserve better attention. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. During the shooting, the main challenge for me was to physically cope to be able to follow on one side a only-night-working photographer (a night which is not a one) and on the other side a dive team who worked during the day, every day. I also had to follow local wildlife and support the scientists in their own work. No rhythm and little sleep. During the editing, the big challenge was to bring the scientific information on physical and biological phenomena which happens at a continental scale, in a expedition story localized in time and space. Every thing without loosing of sight the story of our two photographers…. Keeping a sensitive point of view and not only factual on my characters (penguins included) and on that continent. The balance was hard to find. Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share? The journey, the remoteness (13 days of storm and boat trip to arrive on the spot), the feeling to arrive in a completely different, out of the world … An extremely deceptive impression when we know the impact of Antarctica on the rest of the world, and vice versa. What next? A project which if it happen, will tackle territory sharing, coexistence, wild life, and need for men to find a way to live with inconvenient species.

We reached out to our festival filmmakers to ask them five questions about the experience of making their films.

Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. Director Thomas Winston: The issue of wolves in Colorado can be contentious and polarizing, our goal with this short film was leverage the aspects of the state that all Coloradan’s love, from the natural beauty to the Broncos at Mile High. Then we ponder the questions: What’s missing from the nearly perfect picture? How do you approach storytelling? TW: At Grizzly Creek Films we always want to tell a story that is both compelling and enlightening. What impact do you hope this film will have? TW: We hope this film will be part of a multipronged approach to build tolerance for wolves returning to Colorado. Since the reintroduction of wolves in the northern Rockies, every wolf that has migrated to Colorado has been killed. This effort hopes curbs that trend.

Were there any surprising or meaningful experiences you want to share?

TW: This film was made in collaboration with the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project. In addition to producing films, the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project commissioned in-depth polling by both Democrat and Republican pollsters to assess the public knowledge and opinions about wolves. The most surprising outcome of these polls is that most Coloradans think that wolves still roam free in their state. When they were told that wolves DO NOT live in Colorado, they overwhelming felt they should, regardless of political affiliation. We used these polling results to shape the approach to the films. What next? TW: We are planning to make additional short films for the Rocky Mountain Wolf Project into 2018. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

Contact UsJackson Wild

240 S. Glenwood, Suite 102 PO Box 3940 Jackson, WY 83001 307-200-3286 info@jacksonwild.org |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed