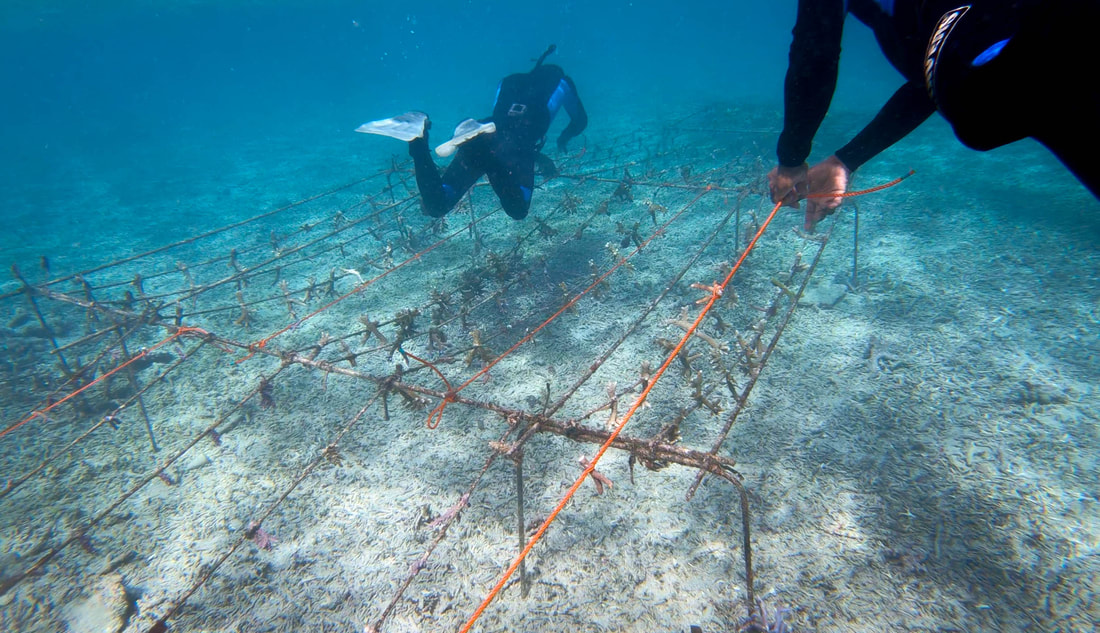

Filmmaker Q&A with Alizé Carrère, Director/Producer of ADAPTATION: Coral Reefs of Vanuatu11/18/2022 Q: What inspired this story? In 2015, I was looking for stories about how people and communities around the world were adapting to profound environmental change. I was working on a film series that would hopefully capture what ‘adaptation’ looked and felt like not as a concept, but as a real lived experience for the millions of people who have no other choice. Around that time I came across the NGO Rare and their Solution Search contest. Solution Search was a call for anyone around the world to submit adaptation projects that were being implemented on the ground, with the hope of sharing and scaling some of the projects. I reached out to Rare and asked if I might be able to access the contest database for the series I was working on, to get some ideas. I came across an entry from a group in Vanuatu (on the islands of Nguna and Pele) working on composting efforts for a predatory starfish that was decimating coral reefs. The project sounded fascinating, so I contacted the group that submitted. The more I learned the more interesting the story got. I didn’t have funding at the time, so we stayed in touch over email for 3 years until I was able to make it to Vanuatu with my filmmaker friend and colleague Kyle Corea in 2018. Once we got there we were amazed by all of the additional adaptation efforts that were going on, including coral gardening and other impressive efforts to keep the reef alive. Q: Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film. As any documentary filmmaker knows, the funding was a real challenge…! I ended up self-funding the trip to Vanuatu itself because I didn’t want to lose out on capturing the story, but then we had to sit on the footage for 2 years before I was able to find the money to actually make the short film/episode. It was thanks to Pacific Islanders in Communications (PIC) that we got a grant to finish it. I had met Cheryl Hirasa of PIC through The Redford Center when I was a grantee there in 2018, and Cheryl really helped us get the short film done. It was through PIC that we were then put in touch with PBS, who ultimately provided the remaining funding to finish the whole series. Q: What's next? Now that the series lives on PBS, we are talking with them about a season 2 of Adaptation. The next batch of episodes will look at what adaptation means not as a technical or mechanical solution to an environmental problem, but rather adaptation as something deeply social and political – because it is! Successful adaptation to the challenges of climate change will ultimately depend on how well equipped and supported a community is in ways beyond financial means. For example, what policies are supporting or hindering resilience and adaptability? Are those policies just, equitable and intergenerational? How are people advocating for their future? Who is bearing the greatest adaptation burden and what can be done to distribute that burden more equally? These are the types of questions I am currently working on in my PhD research on climate change adaptation and that are critical to invoke in film projects covering climate change as well. Keep up with Alizé and her work on Instagram.

4 Comments

Filmmaker Q&A with Yaz Ellis and Jack Mifflin, Directors and Cinematographers of Beavers About Town11/11/2022 Q: What inspired this story? This story is a passion project for us. We had never seen a beaver before we moved to Austria and so we wanted to find out more about these hard-working animals and what secrets they might have, living in the city of Vienna. After months of trying to find the best filming location, we realised one day that there was a family of beavers right below our feet, living under the very steps we were standing on. Once we had discovered this family we followed them on their early morning, evening and night time adventures and created Beavers About Town. Q: Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film/program. We both worked on this film around our jobs, with only a minimal budget. This meant we had to get creative with the gear we had. We converted our Canon 5D MKIII into an infrared camera, after following a tutorial online. We had to tie down our GoPro with branches and stones to get the underwater footage of the beavers. We then had beavers stealing and moving our underwater GoPro, which meant unplanned dives in the Danube in order to retrieve our gear - the water was about 10 degrees celsius at the time! When we started creating the film we faced covid curfews at the hours beavers were most active, majorly restricting our filming. And in order to get to the beavers we had to travel for an hour on public transport. But as these beavers are active so early in the morning in the summer (before the trains are running), this meant a 13km bike ride through Vienna, at 3am with our gear on our backs. And then cycling back 13km at 8am, ready to start work for the day. Q: What is your favorite shot and why? When we filmed the beavers on their “summer picnic”. A beaver swims up to a tree in the water and reaches up with its hands to strip bark from the tree and eats it. The light was perfect that evening and the reflections were incredible. It was also the closest a beaver had physically come to us whilst filming, and was the beginning of the film becoming a reality for us. Q: Did the film team use any unusual techniques or unique imaging technology? We wanted to film the beavers living under the stairs without them even knowing we were there. As mentioned, we converted one of our cameras to see infrared light, which is not a visible light for beavers. We found a gap in the steps just big enough to fit our camera and an IR light in, which we placed inside while the beavers were out feeding. Then as they came back one by one we filmed them grooming, eating and falling asleep without them even knowing we were there. We also used the IR camera to film the beaver inside the boat. For this we had to tape the camera and lights to a branch that the beavers had stripped the bark from, and hold it as steady as we could while the beavers swam into the boat and cleaned themselves. Q: What impact do you hope this film/program will have?

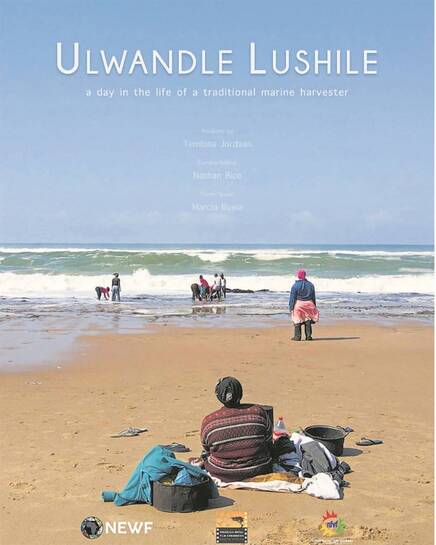

We hope this film is an inspiration for how wildlife can thrive alongside us in our urban environments; and shows that the beaver is a living example that we can still bring animals back from the brink of extinction. And for the continued beaver controversy out there - we hope that it proves the beautiful, resourceful, loving and peaceful animals that beavers are. Tembisa Jordaan is a marine scientist and filmmaker, currently working as a manager for biodiversity, economy and stewardship at Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife. She believes that filmmakers and scientists often impose a perspective and bias into stories of their focus communities. Tembisa strives to do the opposite–to elevate the stories she finds in communities, to see the environment from the community’s perspective, and provide a platform for them to tell their own stories. This is exactly what she does in her first film: Ulwandle Lushile: Meeting the Tides. “Ulwandle Lushile” loosely translates from Zulu as “the sea is dry,” noting the best time for mussel harvest--which is what the film is about. But it’s not just about mussels. This film brings into perspective South Africa’s apartheid history and its impact on natural resources management--in this case, the mussels. This film, which won second place in the Yale Environment 360 Video Contest follows the Sokhulu women who rely on mussels as a significant source of food, relearning sustainable ways of harvesting the mussels that existed years before the apartheid regime. As apartheid came to an end in 1998, the Marine Living Resources Act allowed local communities to access places that apartheid had previously restricted. This brought a new wave of adjusting, relearning, and passing down the indigenous knowledge that past communities practiced to sustainably harvest and consume mussels at the shores of South Africa’s province, KwaZulu-Natal. What inspired this story? The story was right before me when I worked as the Resource Use Ecologist, implementing the mussel harvesting programme in KwaZulu-Natal. My main motivation was from seeing the gap in the science and the story. Coastal communities are often just told what to do without fully understanding how that will impact their livelihoods, so the aim of this story was to bring back the local voices and give the story about marine conservation a human component. Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film/program? My biggest predicament while shooting was the issue of tides. There's a limited amount of time to harvest because of tide times, and the shooting time was not during spring low tides. The second thing has to be the issue of compensating characters for time spent on the project. I know that industry has such strong opinions about how that might influence the story, but I feel it is unethical to expect people to take time away from their work or other means of survival to shoot for many hours for free. The same way that we budget for the camera work and editing is the same way we ought to consider some form of remuneration for our characters, especially ones who take from nothing. What did you learn from your experience making this film/program? Storytelling is a powerful science communication tool and it really does come naturally for us Africans, because our whole history and lineage is told from one generation to another, through the stories told by our Elders. What impact do you hope this film/program will have? I hope it motivates South Africans to start doing something for our people and stop waiting on the government to do something. I would like for this film to infiltrate the academic space and influence black scientists to start looking at science from a people-centric perspective, and to do the needed work to show that Africans have always been one with nature. Conservation is in our blood. How do you approach storytelling? I create a conducive platform for local voices to be heard and to show the indigenous knowledge that is still intact. I also remove myself from the story, as a point of interest, and shine a light on the important stories that Africa and the world at large need to see. I just want to capture the beauty of our thought process and value systems where conservation is concerned. What’s next for you? For the film? More coastal stories, lots of cooking and hopefully a non-profit organization that focuses on finding sustainable livelihoods for communities, support and knowledge exchange. What is your take on the role of storytelling in promoting sustainable lifestyles and sustainable use of natural resources? With storytelling, especially in films, if you are able to nail down the key areas that you want to address in your story, it drives the human emotions about who it directly impacts. For example, if you want to communicate the impact of littering, you can tell a story of how their more often unintended actions impact the livelihoods of someone else. As naturally compassionate beings, seeing the visual impact of our actions can drive change now that we see the end results of our actions. Storytelling changes people’s perspective quicker and can do so in influencing sustainable living. About the Author: Irene Marra is an Operations Associate at Jackson Wild. She is currently pursuing a BA in International Business and Trade at the African Leadership University in Rwanda, with a passion for entrepreneurship, storytelling, and digital content creation

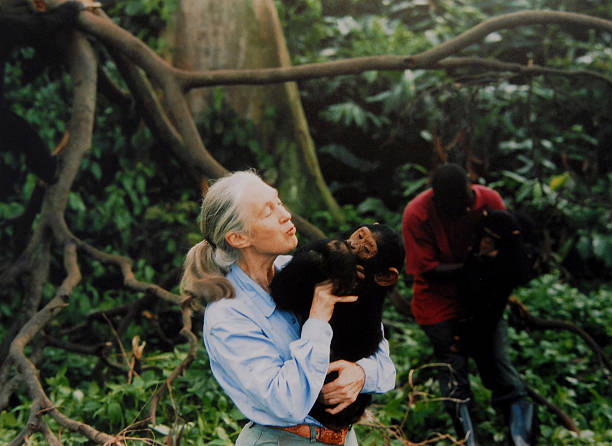

How often do you sit and think: “are we as humans unique? Do humans resemble another species?” Probably not very often. We might think we are unique until we meet our “cousin”: the chimpanzee! Humans and chimpanzees share about 99% of their DNA, the closest the two share with any other species. The next time you see a chimpanzee - don’t be shy, say hi! You have probably seen and heard a lot about chimpanzees today. It’s only natural as today is World Chimpanzee Day. This day celebrates chimpanzees, raises awareness on the challenges they face, and promotes their protection and conservation - thanks to Jane Goodall. July 14, 1960 is when Goodall began studying chimpanzees at Gombe National Park and has since become an inspiration to scientists and researchers focusing on chimpanzees. Over the years, there have been some amazing discoveries and learning about chimpanzees. Let’s take a closer look at some of the most interesting social resemblances between us and chimpanzees. Empathy and Friendship Do you have a best friend that you relate to and care for? So do the chimps! Research shows that chimpanzees have the ability to empathize with others emotionally and can even form close bonds and friendships. Anthony Ochieng, a Jackson Wild award winner and founder of TonyWild, narrates a story of the chimpanzees’ human father in Uganda. “Papa,” as they call him, speaks of being bullied by other chimpanzees while one of them becomes very friendly and empathetic. Sophia, the empathetic chimpanzee, has a best friend called Megan - amazing, don't you think? Cognitive Abilities Imagine a chimpanzee beating a human at a memory test with sequences and numbers. Sounds unreal, right? But it's real! Ayumu, a chimpanzee at Japan’s Primate Research Institute, did it and so can other chimpanzees. These members of the big 5 apes can understand, connect, and memorize pieces of information almost the same way that humans can. Their abilities manifest in their social relations where they cooperate on tasks such as food gathering and coping with various cultures - yes they do have their own cultures! Coordinated War Chimpanzees are calm, peaceful creatures until they get angry - sound familiar? Similar to humans, due to their cognitive abilities and social communication skills, chimpanzees are able to plan and wage war on other members of the species. Studies have proposed that this is an adaptive strategy, for example, when one group attacks another group to obtain food and other resources. Male chimpanzees especially can get aggressive when triggered by members of rival communities. These are just a few examples of how alike humans and chimpanzees are. It is also important to note that despite the acute resemblances between human and chimpanzees, we still remain distinct from each other. We can and should love and care for chimpanzees without necessarily humanizing them. One of the ways we can achieve this is through thoroughly educating ourselves about the species. The best way to learn more about chimpanzees is to go trekking in various parks - there, you will find practical knowledge and rich information that will help you understand our cousins better. One of the things you’d learn is that chimpanzees are endangered due to habitat loss, disease, and hunting. Park rangers and other experts can help you learn what you can do about it as a citizen, conservationist or storyteller. About the Author: Irene Marra is an Operations Associate at Jackson Wild. She is currently pursuing a BA in International Business and Trade at the African Leadership University in Rwanda, with a passion for entrepreneurship, storytelling, and digital content creation. “Living at altitude in the freezing mountains might not be ideal but at least the view will be stunning.” Wildlife filmmaker Ana Luisa Santos produced a film in 2017 about the lammergeier, also known as the bearded vulture. “It won my full respect,” she said about the species – her first pick if she could switch bodies with any animal on the planet. “This scavenging bird is able to fully close the cycle of life due to its incredible ability to eat and digest bones. Super beautiful, strong, unique, and sustainable.” There’s no one path to becoming a wildlife filmmaker, but Ana Luisa’s journey is particularly unique: she started her career as an engineer. “To be trained and educated as an engineer gives me the possibility of understanding, analyzing, and telling a story from a different, more logical perspective,” she said about how her engineering background has influenced her storytelling. “I like building sequential blocks and simplifying the idea I want to transmit. The natural world is already a complex system. It is crucial for me to tell the story as simply as possible, ensuring a complete understanding of the message and information. The better that the viewer understands it, the more chances it raises awareness towards a better planet.” After settling in The Netherlands, Ana Luisa put her engineering career on hold to dedicate herself to filmmaking full-time. Spending considerable time in the field, her work covers all the stages of production from concept to delivery. Her mission is to tell stories about real animals with wild behavior. While she loves the thrill of seeing projects through to the finish line and changing minds across the globe, she faces her fair share of obstacles in the field. “Finding and filming animal behavior in the wild is getting increasingly challenging. Human actions and choices are having a huge impact on the natural world. For example, there is always plastic in nature, regardless of how remote it is,” Ana Luisa shared about her struggles in the field and the effect of humans on the wildlife she captures. “The ecosystems are being damaged by our decisions and actions. We are all responsible, and we must act now.” Ana Luisa uses the Jackson Wild Collective to stay connected to other filmmakers in the industry. “It opens the door for communication and inclusivity, making its content and resources available to all. A massive highlight is that it is free to sign up, giving a chance to academic individuals or industry professionals to be updated regarding new opportunities that might arise.” Hard work and personal sacrifice were crucial to getting Ana Luisa to where she is now. As one of the only female Portuguese wildlife filmmakers, she had to pave the way for herself. “At this point on my journey, I am certainly proud of being able to find a level of stability that working hard allowed me to have. I found a balance in my life that helps me keep my feet on the ground always with my eyes on the future.” With almost a decade of experience in the industry, she provided some great advice for aspiring wildlife filmmakers: “It is a hard industry. Most likely, you will receive more negative than positive responses for that great idea you thought could change the world. It happens all the time. But keep this in mind: you don’t need to convince the entire world about what you can do. You just need the right person to believe in you and give you an opportunity. Keep fighting – the good things can happen!” Ana Luisa stays busy running her production company Ateles Films, as well as working on other projects. She’s currently working on a feature-length blue-chip wildlife film about an underrepresented species that lives in Western Africa, highlighting its behavior, beauty, and importance in what remains of its habitat. She is also developing an IMAX project which explores the local fauna and flora of the Netherlands. “It’s a great opportunity to develop new creative skills and learn new techniques that are very different from producing or directing for TV broadcast.” Keep up with Ana Luisa’s work at Ateles Films by following along on Facebook and Instagram, or visiting her website. The Jackson Wild Collective is the virtual home for our global storytelling community to connect, collaborate and inspire change year-round. Join today.

Q: What inspired this story? Everything begun from a question that we made to ourselves: if there was a time that humans and wild animals needed to be friends and cooperate for surviving in the wild, what remains today about that? What remains from the connection hat we have lost. At the very beginning we had the idea of making a feature documentary about the last relations of symbiosis between humans and wild nature all around the world. But after more and more research we realized that we could join as couples many of the stories. Thats why finally each chapter has 2 stories that work as a mirror one with each other. Q: Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film/program? In some places the climate was hard. For example in Mongolia we were sleeping in tents at -18Cº for a month. The batteries and cameras suffered a lot. In South Sudan or Ethiopia the security sometimes was a must and looking for hyenas in Harar city in the middle of the night was a challenge too. In Perú we worked at more than 5000 meters above the sea level for capturing the vicuñas. We needed to try for twice because the first time the people from the community couldn’t capture anyone. More than 70 people went walking to the top of the mountains for nothing… but we finally made it. The team behind the scenes was small. 4 people have been traveling along 11 countries nearly without a break. Sometimes we felt exhausted but the commitment and the passion of the crew was incredible and we achieved what we were looking for. Q: What did you learn from your experience making this film/program? Many learns… I couldn’t make a list. 11 countries, many emotions, stories and experiences. Maybe one of the most important ones: you can find the greatest beauty of the human being in people like the main characters of the series. Because they are still much closer to what we really were during the origin of our species. And this is a good reason to support the conservation of our planet I think. Q: How do you approach storytelling? The way that we work takes a lot of effort during the preproduction phase. The two directors study a lot about each ethnic group(publications, anthropological studies, articles…) and the main characters that will be the protagonists of the chapters. Before going for filming there is a study on field made by the local producer. The local producer receive all the doubts and ideas from the directors after theirs studies. Is a very interesting way to have a first idea of what is honestly real from what you have studied or read and contrast it with the reality. According to the info that we receive from the local production, we compare it with the bibliography that we have studied and the writing of the fist script starts. With that first script the shooting crew travel to the country where the story will take place. The first contact with the people is very important so we don’t usually take the cameras until the 3th or 4th day. Once we know the people and we discover who will finally be the main character we start with the interview. The interview is very long and deep, in the case of the mongolian story it took more or less 13 hours of questionary. After each day of interview, it is made a translation that works for prepare the shooting of each scene according to the words of the character. The script evolves day by day with the new infos and the way you can shoot the scenes. And in the case of this series due to the structure in which each chapter has 2 parallel stories we tried to make a storytelling that could work as a mirror. Q: What impact do you hope this film/program will have? We hope this series will be a great chance for inviting to our society to reconnect with the nature. Is a chance for having a conversation with people that apparently don’t have nothing in common with but you realized that yes. All of us, it doesn’t mind from where you are, your culture or your color, belong to the nature. And inside each one of us there is a feeling of love to the animals and nature because there was a time that we were part of the ecosystems as a one more wild element. The main characters of this series have been living in a very sustainable way with nature and their environment using their cultural knowledge and traditions. Today governments, fortunately, are investing millions of dollars in conservation but them have been doing that as a way of living since their upper ancestors. And it seems that nobody cares many times about them. During the next 20 years many of the stories of this series will be extinct and with them we will lose an incalculable human heritage. Q: What's next?

We can't talk much about it yet but the team will be working in the Amazon and African rainforest in 2022 for filming some new conservation and indigenous stories. In 2020, Ben Albert spent his summer floating around wetlands in southwest Wisconsin in a canoe. Ben’s grandfather, Cal DeWitt, is a wetland scientist who has lived on and studied the Waubesa Wetlands for over fifty years. The area is one of the highest quality and most diverse wetlands remaining in the state of Wisconsin. Eager to share the story of this less-appreciated ecosystem, DeWitt called up Ben in the spring of 2020 and asked him if he would be interested in making a film about the wetlands and the wildlife who call it home. Just a few weeks after dropping out of film school, Ben agreed and made his way to the area, spending months exploring the wetlands on foot and in the water. Using a telephoto lens, he captured footage of creatures great and small, while also sharing the human perspective of what it’s like to be in a wetland. “As I explored the wetland and learned more from my grandpa, my own perspective changed. I began to see the deeper value and beauty of this ecosystem. Whether it’s a wetland, a local park, or our own backyard, we are surrounded by the hidden wonders of the natural world if only we take a closer look.” Ben Albert is a wildlife filmmaker and member of the Jackson Wild Collective. Now based in Maine as an intern for Compass Light Productions, Ben grew up on a small farm in Wisconsin, immersed in nature. “It was an incredible place to grow up,” he said. “When I was at school in the city, I realized I was missing that part of my life.” He got his start young, picking up a camera and filming his friends when they went skiing. His interest turned towards narrative filmmaking, which allowed him to hone some technical skills and become a better editor and cinematographer. Film school was a logical next step, but after a couple of years, it became clear that he wasn’t on a path toward what he was most passionate about. “I don’t regret it at all,” Ben said about his choice to leave film school. “It was one of the best decisions I’ve made in terms of my career.” Ben was raised on nature documentaries, seeing the wonder of the planet as narrated by Sir David Attenborough. “The natural world is really a magical place that you can lose yourself in. It’s all around us, but these films bring it out in a new light,” he said. He knew he wanted to get more into nature and documentary filmmaking instead of narrative film, so he left school, headed to the Waubesa Wetlands, and never looked back. Ben is still early on in his career, but he shared advice for emerging filmmakers: “Make opportunities for yourself. Especially when you’re just starting out, projects won’t just fall into your lap. A lot of the time, the only thing stopping you is yourself – learn skills online and think about what you can do right now to get yourself where you want to be.” He also shared something he wished he could tell his younger self: “If I were to give myself advice two years ago, it would be to not try and do everything by yourself. Everything you do will be ten times better if you bring in others.” The Jackson Wild Collective has helped Ben put that advice into practice. “I think the map feature is one of the best parts; I’ve connected with people all over the world,” he said. Ben joined the Collective after the 2021 Jackson Wild Summit. “When I first thought about making this my career, I felt like there was a huge gap between where I was and where I wanted to be, between emerging and established filmmakers. The Collective bridges that divide, connecting people with different skill levels and experiences into one space together. It breaks down barriers and reminds us that we’re all people, we can all support each other.” Ben continues to work on Waubesa Wetlands - An Invitation to Wonder; you can view the trailer HERE. Follow Ben on Instagram to keep up with his latest work, and check out his website to learn more about his projects. The Jackson Wild Collective is the virtual home for our global storytelling community to connect, collaborate and inspire change year-round. Join today.

Q: What inspired this story? Executive Producer Jared Lipworth got word that Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique was planning on reintroducing a top predator - African Wild Dogs - back to its ecosystem. He realized that this would be a rare opportunity to tell the story of the key role predators play in the natural world and set about putting the team together that could help make the most of it. Q: Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film/program? The main production challenge was in capturing the African Wild Dogs in their natural element. They move constantly, they move swiftly, and these packs in particular moved unpredictably since they were just exploring their new home - a diverse African landscape the size of the state of Rhode Island. The biggest story-telling challenge was to integrate the larger scientific investigations within the very specific narrative of these particular African Wild Dogs. In order for us to tell our true story, the "landscape of fear" scientific theory needed explaining and contextualizing, the park's history needed to be laid out, and the various human characters needed to be introduced and profiled all the while not losing the momentum of the narrative. Q: What did you learn from your experience making this film/program?

I learned that African Wild Dogs – otherwise known as Painted Wolves or Painted Dogs – are an incredibly charismatic and tragically endangered species. Like many predators, they have been targeted for extermination in the past. Fortunately, there are some heroic efforts underway to reintroduce them to appropriate areas, including Gorongosa. In making this film I also came to a deeper appreciation for the role of predators in wild ecosystems and their importance in establishing and maintaining a healthy balance between the various species. Q: How do you approach storytelling? I approach storytelling as a journey. I was an English major in college, but I firmly believe that the truth is always more interesting and useful than anything you could make up. With each project I am learning something new, meeting new people, exploring a new part of the world. For me, the most successful projects are the ones that somehow take the viewer on the same journey I have gone through and allow them to share in the discovery, excitement, and surprise I have experienced along the way. Q: What impact do you hope this film/program will have? I hope people who see Nature’s Fear Factor will have a greater appreciation for nearly everything in the film – the role of predators in general and African Wild Dogs in particular; the importance of national parks like Gorongosa; and the dedication and intelligence of the scientists and conservationists who devote their lives to wild places and the animals who depend upon them. I also hope viewers will come away with a sense of hope, that rewilding can succeed and that Nature can rebound if given the chance. Filmmaker Q+A with Geoff Luck, SVP Creative & Production of Wild Elements Studios: Greens for Good5/9/2022 Q: Describe some of the challenges faced while making this film/program?

This film was shot in Liverpool in December of 2020. Given limitations due to the pandemic, this meant collaborating with a remote UK-based team who had to work within a narrow window between lockdowns—and to do so as carefully and responsibly as possible. Each scene was evaluated for safety as well as storytelling significance, and involved the planning and input of all concerned. The creative approach to the piece was thus built in stages, with the initial approach determined by Farm Urban and the US team then handed over to the UK production team who then worked with the subject on its realization, only to then pass it off again to a post-production team back in the States. Despite—or perhaps, because—of these many voices, the piece came together as a mutual expression, one enriched by each person that had a (sanitized) hand in its production. Q: How do you approach storytelling? Before making this film, the creative team at Wild Elements spoke with the subjects at Farm Urban about what was most important for them about their work. They mentioned specific programs and how they operate, the way they engage the community and the benefits they offer, as one might expect. But most of all, they described a point of view. One that spoke of social and environmental justice, the possibilities of human invention and collaboration, the centrality of caregiving and community. So we put this at the forefront of our efforts, and sought ways to evoke—or even more simply, to recognize—the depth of the team’s commitment to their work and those they work with and for. Any of that that comes through is a direct result of the leadership offered by the Farm Urban team themselves, the connections they forged with the UK production team, and the way that showed itself in the edit room. Q: What impact do you hope this film/program will have? We live in a time when we have to rethink the way we do things—both at the margins of our presence on the planet and in the heart of our sprawling cities. By looking at the innovative ways that Farm Urban couples emerging technologies with innovative social outreach and engagement, we hope the film will compel others to think outside the box of how things have been done to wonder about how they might be done instead. It is then ultimately aimed to inspire urban dwellers to see that our connection to nature starts at home—even if that home seems bound by concrete and high rises. Q: How do you approach storytelling?

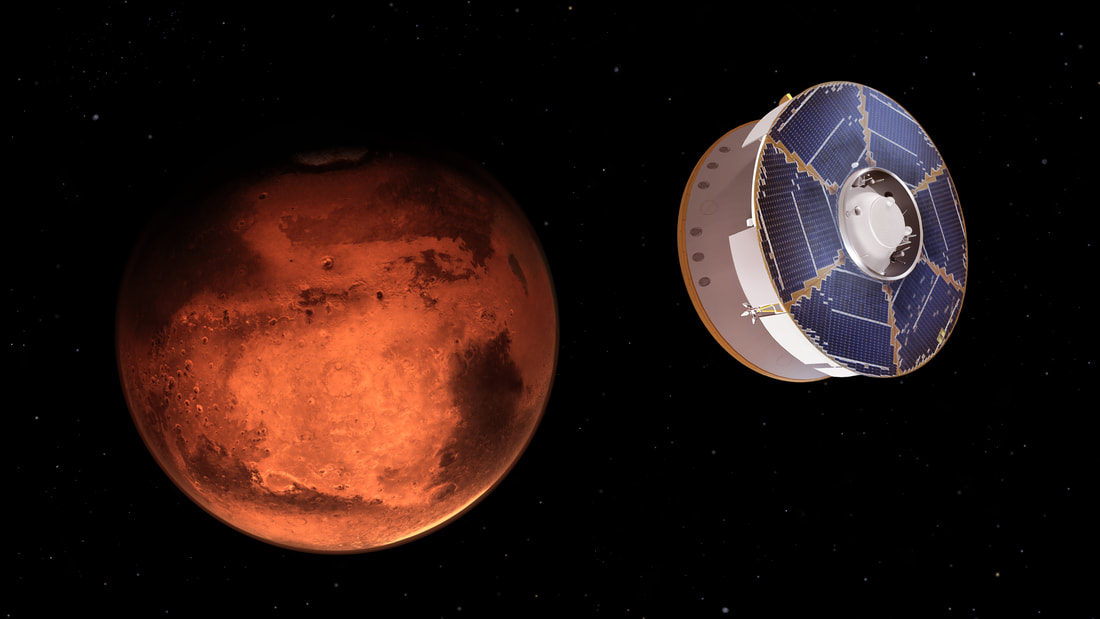

The best stories come from compelling storytellers. I search for scientists who are passionate about their work and excited about the challenges involved and work with them to develop ways to tell their stories and translate their work into language the rest of us can understand. For me, that’s the biggest challenge in science programming, finding ways to personalize the story. Q: What impact do you hope this program will have? From landing a rover on Mars to flying a tiny helicopter named Ingenuity on another planet, the scientists featured in “Looking for Life on Mars” are inspiring. I hope their stories help people understand what kind of collaboration and dedication it takes to engineer this kind of space mission, as well as motivate aspiring young scientists to pursue their dreams. Q: What’s next? I’m currently producing an hour for PBS/NOVA about the James Webb Space Telescope, launching sometime this year. It is the most complex space telescope ever built. Consequently, the mission has had a difficult time getting off the ground. But if all works as planned, it will revolutionize the world of astronomy. We’re following several scientists on the mission to see how their stories unfold and if years of hard work will pay off. |

Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

Contact UsJackson Wild

240 S. Glenwood, Suite 102 PO Box 3940 Jackson, WY 83001 307-200-3286 info@jacksonwild.org |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed